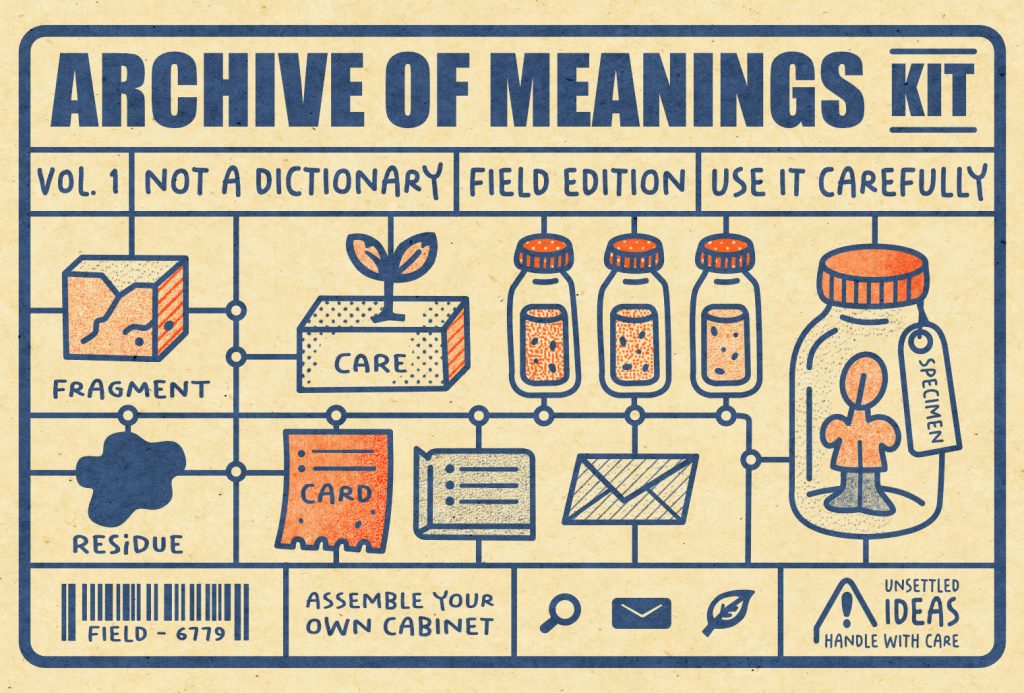

This cabinet of definitions gathers concepts, methods, and fragments that have guided my work over time. Like specimens in a drawer, each entry here displayed is less a fixed meaning than a provisional arrangement: a label, a story, or a partial definition. Some of these terms are coming from anthropology and STS; others are borrowed, reinvented, or improvised in the field. Together they form a living lexicon—an assemblage of words that accompany experiments in ethnography, more-than-human encounters, and curatorial practice. Rather than offering authoritative explanations, this cabinet invites readers to open drawers, browse, and make their own connections across entries.

A

Animal enclosures

Animal enclosures are urban infrastructures where domesticated or farmed animals live under human surveillance. Unlike traditional zoos, they host goats, sheep, ponies, or poultry, inviting visitors—often children—into structured forms of contact. These spaces blend leisure, pedagogy, and captivity, creating hybrid settings where multispecies encounters unfold under uneven conditions. Enclosures are both community hubs and sites of control, organizing relations through fences, feeding routines, and pedagogical programs. They reveal how cities stage proximity to other beings while maintaining asymmetry.

Attunement

Attunement is a practice of listening and noticing that lingers with fluctuation, rhythm, and incompleteness. It resists quick stabilization, allowing the world to be sensed as unfolding rather than fixed. In ethnography, attunement asks the researcher to stay with the shimmering edges of events—the pauses, gestures, and atmospheres that escape categorical capture. More than method, it is an ethic: a way of writing-with rather than writing-about, cultivating receptivity to what becomes in the intervals of relation.

C

Cabinet

A cabinet is both storage and staging. It gathers fragments, specimens, and concepts into drawers or compartments, arranging them for future encounters. More than a container, a cabinet is a curatorial device: it orders while inviting discovery, conceals while displaying, stabilizes while allowing drift. Cabinets are never neutral; their selections shape what is remembered, compared, or imagined. As ethnographic method, the cabinet turns research into collection—an assemblage of partial worlds waiting to be opened, browsed, and recomposed.

Captivity as infrastructure

Captivity is more than a moral condition; it is an infrastructure that shapes multispecies relations. Fences, barns, and enclosures organize proximity, setting the terms of who can move, touch, or be seen. These structures both constrain animal life and enable encounters between humans and nonhumans. As infrastructure, captivity is material and relational: it scripts daily routines, directs care, and produces uneven freedoms. It reminds us that spatial technologies of control mediate multispecies engagements in the city.

D

Distribution

Distribution is the movement and scattering of materials, stories, or relations across space. It organizes who has access to knowledge and how it travels. Far from neutral, distribution is political: it creates paths of circulation while also producing exclusions. To follow distribution is to attend to the infrastructures and practices—formal and informal—that enable fragments to reach others. It is less about final arrival than about tracing the uneven routes through which things, beings, and ideas circulate.

F

Folding

Folding is both method and metaphor: the act of bending materials, texts, or spaces so they overlap and reveal hidden surfaces. In ethnographic practice, folding allows fragments to coexist without erasing difference, layering times and scales into a single page. A fold is not closure but invitation—an opening that multiplies perspectives. In Tarde, folding organizes the zine’s provisional format, where narratives, images, and textures crease into one another, generating encounters across disparate urban scenes.

Fragment

A fragment is a piece detached from a larger whole, though the whole may never have existed. Carrying traces of rupture, fragments appear as residues, ruins, stains, or snippets of speech. They resist closure yet invite interpretation and arrangement. Working with fragments means valuing incompleteness as a mode of knowledge. Each fragment hints at broader worlds while remaining partial and situated. Their unfinished nature turns them into fertile grounds for speculation, care, and experimental forms of ethnographic storytelling.

Friction

Friction is the resistant contact that occurs when surfaces, beings, or ideas rub against one another. It produces delay, discomfort, and energy, making relations visible through their rough edges. Rather than smoothing differences, friction highlights asymmetry and contradiction. In ethnography, it draws attention to how encounters are never seamless but shaped by tension and negotiation. Friction is both an obstacle and a catalyst: a condition through which transformation, awareness, and alternative possibilities emerge.

G

Grammatical Risk

Grammatical risk refers to the vulnerability of loose language. It occurs when ethnography suspends the safety of nouns and experiments with verbs, atmospheres, and dissolutions. Risk here is not error but exposure: the chance that writing may blur clarity while opening new sensitivities. It is a wager on form, where description becomes invention. Grammatical risk is methodological courage—the decision to write otherwise, knowing that what emerges may be unstable, but also generative of new ways of sensing.

I

Idealism spectrum

The idealism spectrum is a heuristic for modulating intensity in ethnographic writing. At one end, nouns remain but tremble, thickened with verbs. In the middle, objects dissolve into mediations and processes. At the far end, only verbs persist, rendering the world as flicker and becoming. This spectrum is not a doctrine but a set of stances—grammatical postures that let ethnographers tune their descriptions differently. It invites oscillation, experimentation, and sensitivity to how language shapes what can appear

Imperfection

Imperfection is the trace of what does not fit: the crack, the smudge, the uneven cut. It resists ideals of wholeness and exposes process rather than polish. In ethnography, imperfection appears in incomplete notes, blurred photographs, or failed attempts—reminders that knowledge is always partial. Rather than error, imperfection is a method: it invites care, openness, and creativity in assembling fragments into provisional forms.

Invasiveness

Invasiveness describes more than ecological intrusion—it is a mode of relation marked by movement, entanglement, and unintended consequence. Often framed as a threat or contamination, invasiveness exposes the politics of belonging and control that define whose presence counts as natural. In ethnography, it gestures toward the porousness of boundaries: how researchers, species, and materials cross into each other’s worlds. To study invasiveness is to attend to cohabitation under tension—contact zones where care and disturbance intertwine.

Inventory

Inventory is both a list and imagination. As a practice of storage, it gathers and records objects, fragments, and names, preserving them for future use. Yet every inventory is also inventive: the act of listing creates relations, orders, and possibilities that did not exist before. It is simultaneously archival and generative, serving as both a tool of containment and a means of speculation. Inventory highlights the dual movement of ethnography as both storage and invention, where keeping track becomes a means of creating new worlds.

Irrelevant (seemingly)

The seemingly irrelevant names the details often overlooked: a wrapper in the gutter, the fleeting shadow of a tree, and even an other-than-human ontology. These fragments may appear trivial, yet they disrupt narrative smoothness and unsettle hierarchies of significance. To work with irrelevance is to refuse the dominance of the “important,” allowing minor traces to carry analytical weight. It is an invitation to linger with the peripheral, to let what appears marginal reveal textures of urban life.

L

Labeling

Labeling is the act of assigning names and meaning to things, beings, or fragments. It classifies, preserves, and controls, yet also reveals the desire to make the world legible. In ethnography, labels operate as both tools and traps—organizing knowledge while constraining it. Each label carries histories of power, care, and exclusion. To label is to curate attention, deciding what endures and what fades. The challenge lies in writing labels that open rather than close interpretation.

M

Materialtone

Materialtone is a taxonomy of urban colors and textures, inspired by Pantone but grounded in city fragments. Rusted fences, chipped tiles, fruit skins, and posters become swatches carrying histories of touch, weathering, and decay. Unlike standardized palettes, Materialtones are situated and ephemeral—curating fragile tonalities rather than permanence. As both a taxonomy and a diary, they form a chromatic ethnography that reveals the city as a patchwork of textures and hues, resisting uniformity and opening up space for alternative ways of seeing.

Montage

Montage is the practice of cutting and juxtaposing disparate elements to create new meaning. Photographs, sketches, sentences, and residues collide without merging, producing unexpected resonances. In ethnography, montage emphasizes relation through difference: fragments are placed together not to resolve into a whole but to reveal the tensions between them. Each cut is also a connection, a provisional arrangement that opens multiple readings. Montage is less narrative than experiment—an analytic technique that thrives on dissonance and surprise.

P

Partial Encounter

Partial encounters are temporary, structured, and incomplete forms of engagement with more-than-human ontologies. Shaped by degrees of captivity, they allow contact yet remain biased, mediated, and unfinished. These encounters are planned—children petting goats, visitors watching donkeys—but are also unpredictable, leaving room for escape, refusal, or indifference. They highlight asymmetry: humans often seek leisure or learning, while animals are instrumentalized. Still, partial encounters reveal the fragility of multispecies relations, where even brief, uneven exchanges carry the potential to unsettle habits of seeing and knowing.

Perecian Instruction

A methodological disposition inspired by Georges Perec’s call to attend to the infra-ordinary—to what recurs without notice. Rather than seeking meaning in the exceptional, the Perecian instruction trains observation on the banal, the repetitive, the overlooked. It transforms description into an ethical and aesthetic exercise of attention: listing, exhausting, inventorying. In ethnographic practice, it becomes a discipline of noticing—an art of remaining with what barely appears, allowing method to arise from the ordinary itself.

R

Region of Usefulness

An unfinished epistemological tool for grasping the multiplicities of urban life. A region of usefulness describes the temporary stabilization of heterogeneous elements—humans, devices, gestures, affects—gathered in-order-to-do-something. It is both material and semiotic, spatial and temporal, continuously reconstructed through relations of use. Emerging from the decomposition of a traffic light in Times Square, it proposes a way to map and think with the effervescent, situated, and relational nature of urban assemblages.

S

Sensory Misclassification

Sensory misclassification foregrounds the generative power of error. A smell mistaken, a color misnamed, or a texture misread are not failures but opportunities to unsettle taxonomies and reveal their fragility. In fieldwork, such slips turn confusion into method, showing how humans and nonhumans inhabit shifting sensory registers. Rather than correcting mistakes, this practice embraces drift, improvisation, and ambiguity—opening space for alternative orders of sensing and knowing.

Specimenography

Specimenography is a method for curating fragments—bones, stains, stories, or images—into provisional specimens. Unlike the fixed authority of the museum, it emphasizes incompleteness, care, and ethical attention. Each arrangement resists singular meaning, staging fragments in relation to one another so that new connections and taxonomies can emerge. Both analytic and poetic, specimenography transforms research into a cabinet of partial worlds, where residues and remains become invitations to linger, imagine, and reconsider what constitutes knowledge.

T

Taxonomy

Taxonomy is the practice of naming and ordering beings, materials, and relations. Though it often presents itself as neutral, it is never without consequence. Every act of classification carries histories of authority and exclusion, but also of care, intimacy, and imagination. To create a category is to decide what belongs together and what remains outside. What is named becomes visible, while what escapes a label risks disappearing from collective attention.

U

Unfolding

Unfolding is the act of opening what is layered, hidden, or compressed. It suggests knowledge as a process rather than a form: something that reveals itself gradually, through touch, movement, and time. Unlike folding, which gathers and conceals, unfolding disperses and exposes. In ethnography, unfolding attends to what emerges when fragments are spread out—when lines of relation, once tucked away, become visible. It emphasizes temporality and openness, inviting new connections rather than closing them into order.

V

Verbing

Verbing is the shift from nouns to actions. It treats the world not as a collection of stable things but as processes unfolding—walking, flickering, gathering. In ethnography, verbing resists ontological fixity by writing the city as choreography rather than a container. To verb is to attend to becoming over being, to describe how life moves, mediates, and transforms. It is both a linguistic experiment and a methodological device: a way of sensing the urban through acts rather than objects.

Z

Zine

A zine is a do-it-yourself publication: small-scale, provisional, and experimental. Rooted in punk, feminist, and activist cultures, zines thrive on collage, repetition, and imperfection. They invite participation, allowing readers to become makers as well. In Tarde, the zine serves as an ethnographic tool—a format for assembling fragments of urban life that transcends academic conventions. Its photocopied textures and irregular layouts resist polish, foregrounding process over product. A zine is at once an archive and an event, circulating minor stories through fragile media.