I am writing this theoretical chapter for the edited volume Uneven Toxic Worlds: Anthropological Engagements with Toxicity and Environmental Justice (edited by Camelia Dewan, Raffael Ippolito, and Peter C. Little). The chapter, titled “Toxic Afterlives: Specimenography and the Uneven Residues of Industrial Farming,” proposes specimenography as a conceptual and methodological framework for anthropology to engage with the slow persistence of contamination. It is not an empirical study but a theoretical experiment—a speculative exploration of how anthropology might attend to toxic afterlives through curatorial and fragmentary practices of thinking and writing.

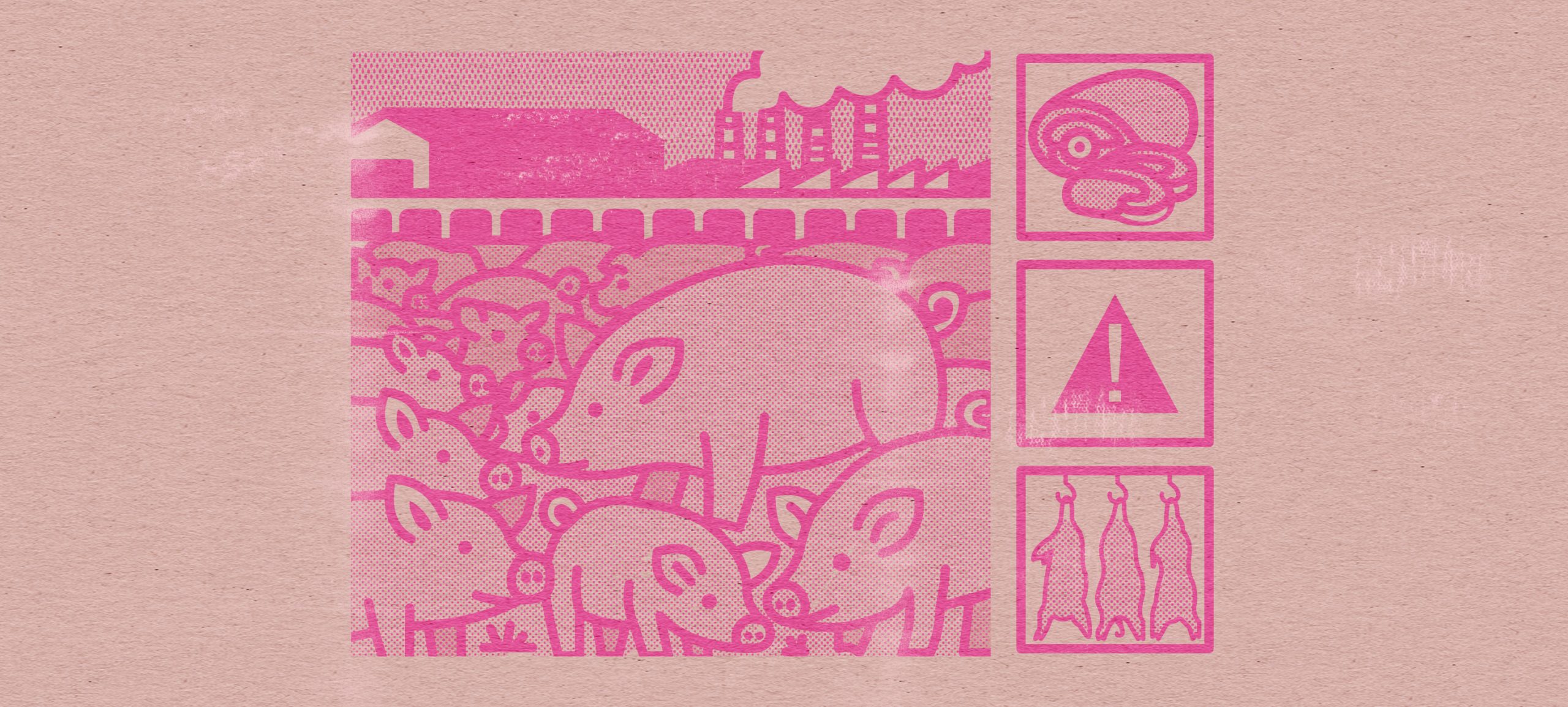

Industrial farming in Europe produces more than meat. It leaves behind a dense landscape of residues—purines, bones, skins, and dust—that persist as ecological harms and political controversies. These residues, often treated as externalities or addressed through techno-solutionist interventions, reveal how toxicity is not a punctual event but an afterlife: a slow and uneven persistence that continues to shape rural environments and multispecies relations long after production has ended.

Through specimenography, I explore how fragments—documents, materials, sensory impressions—can be curated as toxic specimens that make visible the entanglements of contamination, care, and accountability. The chapter suggests that curatorial practice itself can become a mode of theorizing: a way to think through collection, arrangement, and annotation rather than representation. It asks what kinds of justice and attention are possible when the object of concern is not a living organism but a slurry pit, a bone, or a cloud of dust.

By engaging with debates in discard studies, multispecies ethnography, and critical environmental justice, Toxic Afterlives expands the discussion of environmental justice beyond exposure and mitigation toward the ethical and political work of living with residues that endure. It calls for an anthropology capable of curating persistence—attending to the toxic fragments that persist long after the infrastructures that produced them have been forgotten.

This theoretical chapter also marks the first step toward a forthcoming research project that will empirically explore the afterlives of pig farming in Europe—tracing how residues, infrastructures, and forms of care intersect in the landscapes of industrial agriculture. The ideas developed here serve as the conceptual foundation for that larger investigation into the uneven ecologies of contamination, rural transformation, and multispecies endurance.

Ultimately, Toxic Afterlives invites anthropology to think with what remains: to transform fragments, residues, and pollutants into theoretical interlocutors and curatorial challenges for imagining justice in uneven toxic worlds.