From The Atelier Series

Berlin was my first true multispecies laboratory—a city where infrastructures, animals, and humans meet in partial, improvised ways. It was here, in the petting farms of Kreuzberg and Neukölln, that I began to sense ethnography as a more-than-human choreography. These spaces were not symbolic; they were infrastructural, material, and pedagogical. They echoed what Anna Tsing (2015) calls “arts of noticing,” yet demanded a slower, more entangled attention—one that could stay with interruptions, repairs, and non-human rhythms.

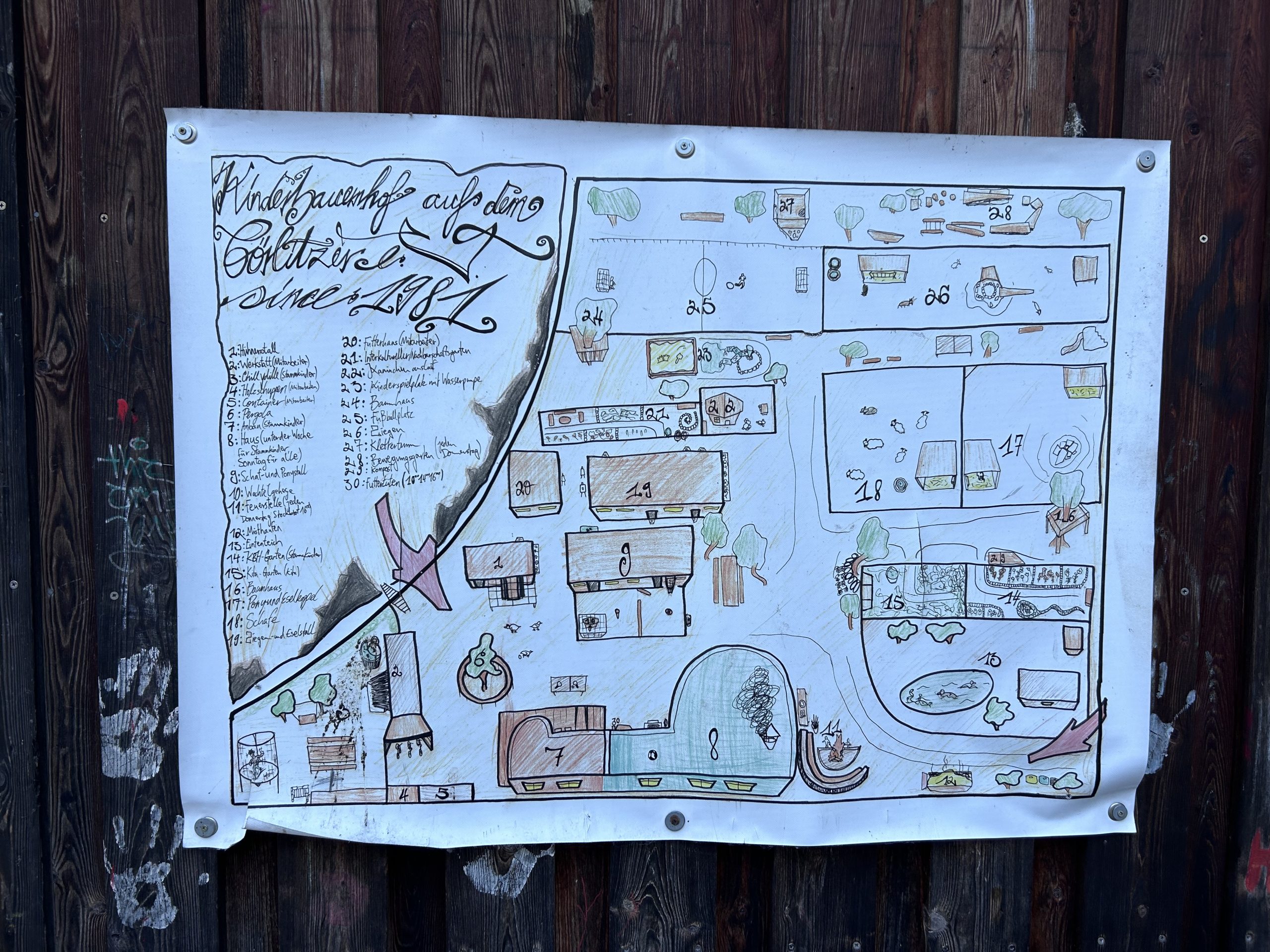

In the Kinderbauernhof of Görlitzer Park, I learned to observe how sheep, children, and caretakers collectively shaped the rhythms of a shared environment. Ethnography became not only about description but about listening through proximity—about inhabiting interspecies timings and care routines. Like María Puig de la Bellacasa (2017) reminds us, care is always partial and compromised, never pure or resolved. It is a matter of constant negotiation.

My concept of partial encounters (Orrego, 2025) was born here. Each observation was incomplete, each relation fleeting. Yet these fragments—moments of feeding, watching, or cleaning—revealed the multiplicity of what coexistence means. I began to understand fragments not as analytical failures but as ontological conditions, following the sensibility of Kathleen Stewart’s (2007) Ordinary Affects: the subtle textures of everyday life as speculative grounds for thought.

Later, at Tierpark Neukölln in Hasenheide Park, my attention shifted from shared presence to the politics of preservation. This farm, dedicated to endangered domestic species, articulated another form of care—care as classification, as taxonomy, as curation. Donna Haraway’s (2008) invitation to “become with” found here a bureaucratic counterpart: living beings rendered legible through charts, labels, and degrees of endangerment.

I began tracing the ethnographic fragment not just as an object of writing but as an infrastructural artifact. A fragment could be a species list, a feeding schedule, or a muddy footprint. Together, they formed a living archive of care practices and interspecies negotiations. Inspired by Michelle Murphy’s (2017) work on alterlife and chemical infrastructures, I came to see these fragments as metabolic residues of urban ecologies—evidence of how maintenance, decay, and interdependence co-constitute more-than-human worlds.

What fascinated me most in these sites was how care leaked beyond intention. Cleaning enclosures, repairing fences, refilling water bowls—these gestures were not simply maintenance tasks but forms of knowledge production. They revealed how infrastructures are made and remade through everyday acts of attention. Ethnography, in turn, became a form of maintenance too: keeping relations open, documenting without closure, inhabiting the ongoingness of care.

In this sense, Berlin became a hinge between experimental method and ethical attunement. The Kinderbauernhof and Tierpark were not laboratories in the scientific sense but what Ignacio Farías (2010) might call “infra-ordinary infrastructures”: spaces where relations unfold beneath the scale of spectacle. Between animals, mud, and maps, I began to sense that ethnography was not about “capturing” encounters but about dwelling in their incompleteness.

Berlin taught me that the fragment is not only a methodological tool but also an ethical stance. It resists totalization, stays with the uncertain, and allows multiplicity to remain visible. The more I wrote, the more I recognized that fragmentation is not the opposite of coherence—it is its condition. The fragment, as Walter Benjamin (1999) and later Stewart (2017) remind us, can be a lens of attention, a form of composition, even a mode of repair.

In retrospect, Berlin was less a chapter than a hinge. It connected the experimental curiosity of my earlier studio practices with the ecological and affective depth that would later define Alterecological Specimenography. Between animals, infrastructures, and traces of care, I found a working principle that still holds: to study the more-than-human world is to stay close to the unfinished—to treat fragments not as remnants of a whole, but as worlds in the making.

References

- Benjamin, Walter. 1999. The Arcades Project. Translated by Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Farías, Ignacio, and Thomas Bender, eds. 2010. Urban Assemblages: How Actor–Network Theory Changes Urban Studies. London: Routledge.

- Haraway, Donna J. 2008. When Species Meet. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Murphy, Michelle. 2017. “Alterlife and Decolonial Chemical Relations.” Cultural Anthropology—Theorizing the Contemporary. https://culanth.org/fieldsights/alterlife-and-decolonial-chemical-relations

- Orrego, Santiago. 2025. “Partial Encounters: Exploring More-Than-Human Entanglements in Berlin’s Animal Enclosures.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 54(3): 336–363.

- Puig de la Bellacasa, María. 2017. Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More than Human Worlds. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Stewart, Kathleen. 2007. Ordinary Affects. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.