Karolina Lukasik, Heta Lähdesmäki, and Toumas Aivelo from the Urban Rats Project have curated this number. This issue was co-produced with Artem Pankin.

Cite this article: Orrego, S. and Pankin, A. 2024. “Rats as urban infrastructures: A tale from two cities.” Tarde 4 (Mar-Apr). DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/Y762A

Content

- Introduction to the issue

- Creating rats, the origin of urban evils

- Rats and the consolidation of the modern city

- Watching rats, a set of visual experiments

- Some pictures from New York

- A Watching Rats alphabet

- Online references

- Handbook references (Medellín)

- Handbook references (New York City)

Introduction to the issue

The conception of cities as multispecies scenarios of cohabitation [1] and confrontation [2] proposes two concatenated set-ups in which, first, nonhumans living in urban areas are involved in different anthropocentric networks, most of the time in asymmetrical power relations [3]. Second, nonhumans are conceived not only as individuals living in human-made urban environments, but also as urban-makers. That perspective distributes the agency of urban production across a plethora of individuals who are constantly producing—in their own ways—new versions of the city space.

This issue of Tarde brings together the ongoing explorations of two rat viewers: one out of curiosity, the other to overcome his phobia of those animals. The explorations were conducted in two locations: New York City and Medellín, Colombia. Our printed version (download it here) compiles a set of vignettes and reflections on rats that produce and interact with urban space in both cities. Meanwhile, this is divided into two sections. The first one introduces a brief story about how rats became villains. The second one presents a set of infographics that display some of our observations and various human-rat encounters observed in both scenarios.

Creating rats, the origin of urban evils

The representation of animals as villains has been a constant activity in human history—the main reason for framing certain animals as enemies was their predatory behavior. However, the nineteenth century was a decisive period when animals were formally accused of acting as “reservoirs and spreaders of diseases affecting humans” [4]. This technical and bacteriological labeling process was quickly enhanced and complicated by the irruption of an already solidified popular concept that originated in the mid-seventeenth century: vermin.

Vermin are “icky, dirty, nasty, disease-bearing animals who are out of place, invaders of human territory. Vermin are animals that it is largely acceptable to kill” [5]. Those creatures have four main characteristics. First, they consume and contaminate human food sources and the production process. Second, they are smart. Vermin often find ways to escape human attempts to catch and control them. Third, they “possessed the ability to manipulate symbols, and even language itself” [6]. Finally, vermin can quickly reproduce and establish large numbers of individuals, threatening to “overwhelm their biological, environmental, and—from a human perspective—sociolegal contexts” [7].

Although the meanings of ‘villain’ and undesirable animal’ have remained unchanged, in modern political, hygienist, and animal-control discourses, the term ‘vermin ‘ has been replaced or, at least, interspersed with ‘pests’. However, and mainly talking about rats, to consider those animals as pests, as disgusting creatures, is just a part of an ontological trifurcation that is also situating them as “lovable (pets) […] and scientifically ‘neutral’ (laboratory animals)” [8]. The difference between evil, good, and neutral rats is a matter of relationships, space, quantity, and, of course, utility.

Rats and the consolidation of the modern city

One of the critical factors in the development and modernization of cities worldwide was the creation of sewage infrastructure. This new technological development “not only removed human waste, it also helped rat populations disappear from view, affording them a new underground home that came to be seen as their natural habitat” [9].

According to Birgitta Edelman [10], disgust, among other things, was one of the main feelings that inspired the planning logic of modern cities. During the Victorian era, “disgust came to be associated with the lower parts of the body. The rejection and abhorrence of everything connected with bodily functions from the waist down was also […] reflected in the topography of cities where covered sewers were constructed to hide and dispose of the refuse.” So, in a clean and modern city, keeping the surface pristine and separated from the disgusting underground was a priority.

However, that is not what happens in Medellín or New York City. Although at different levels, both cities have severe issues managing and disposing of their trash. Plastic bags accumulate daily in the streets, unsupervised filthy containers, overflowed bins, and political lack of care and operation are the main reasons why the cities’ surfaces turn into attractive spaces for rats and other animals.

Watching rats, a set of visual experiments

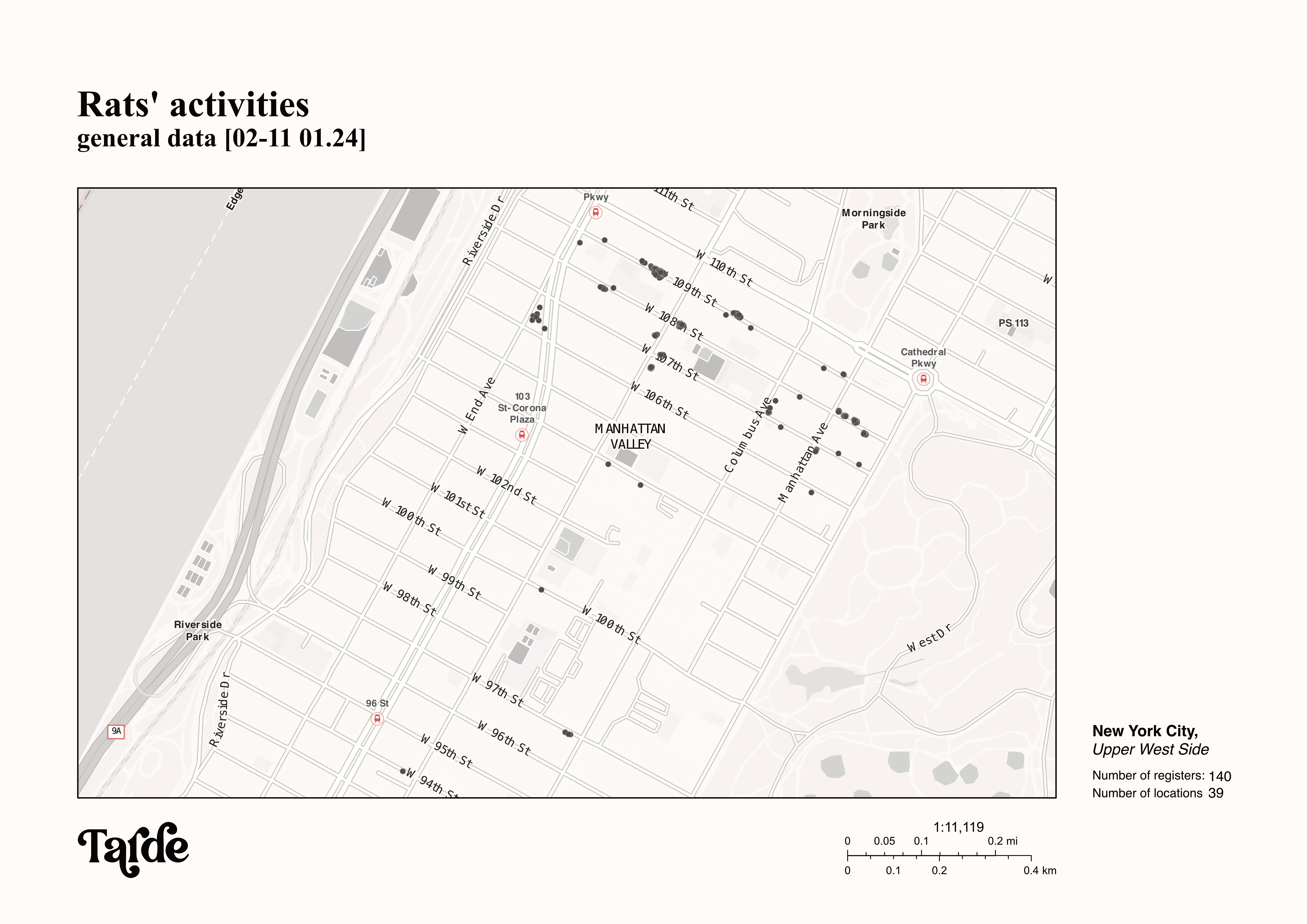

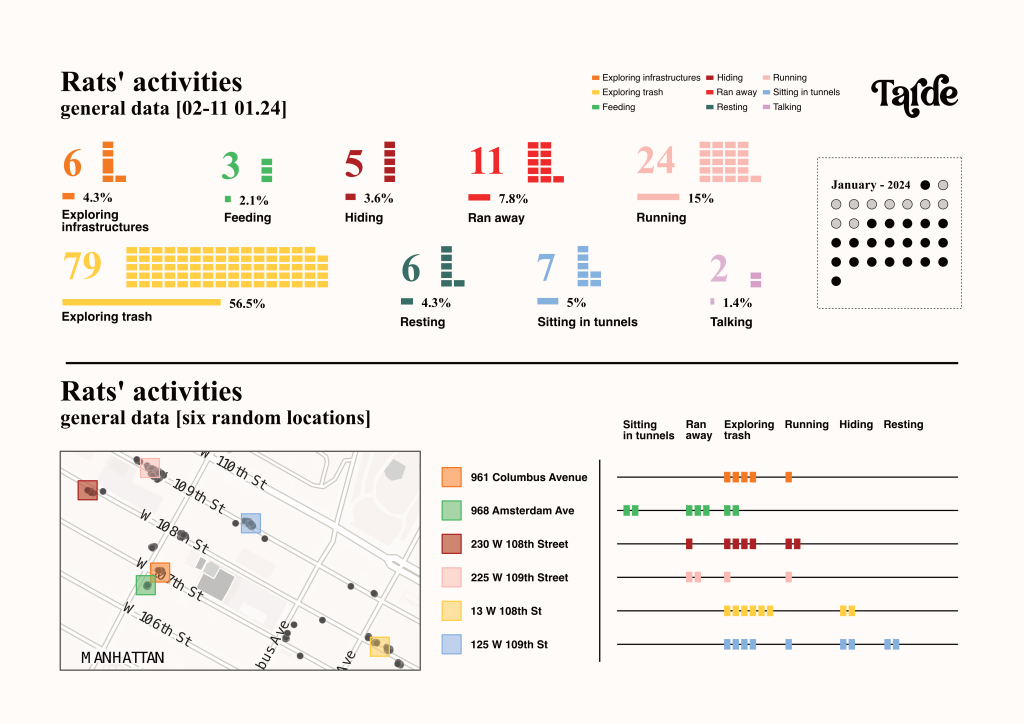

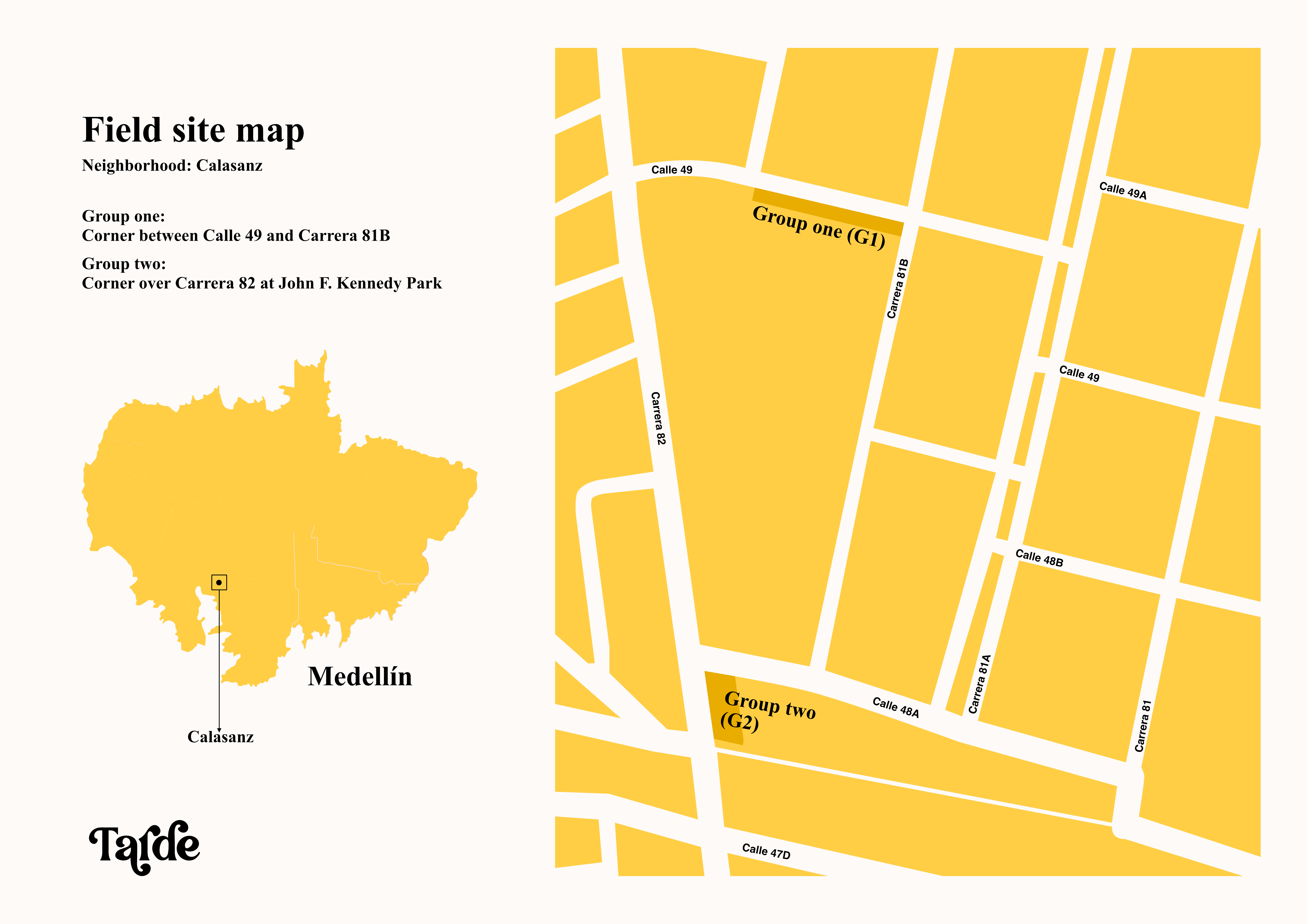

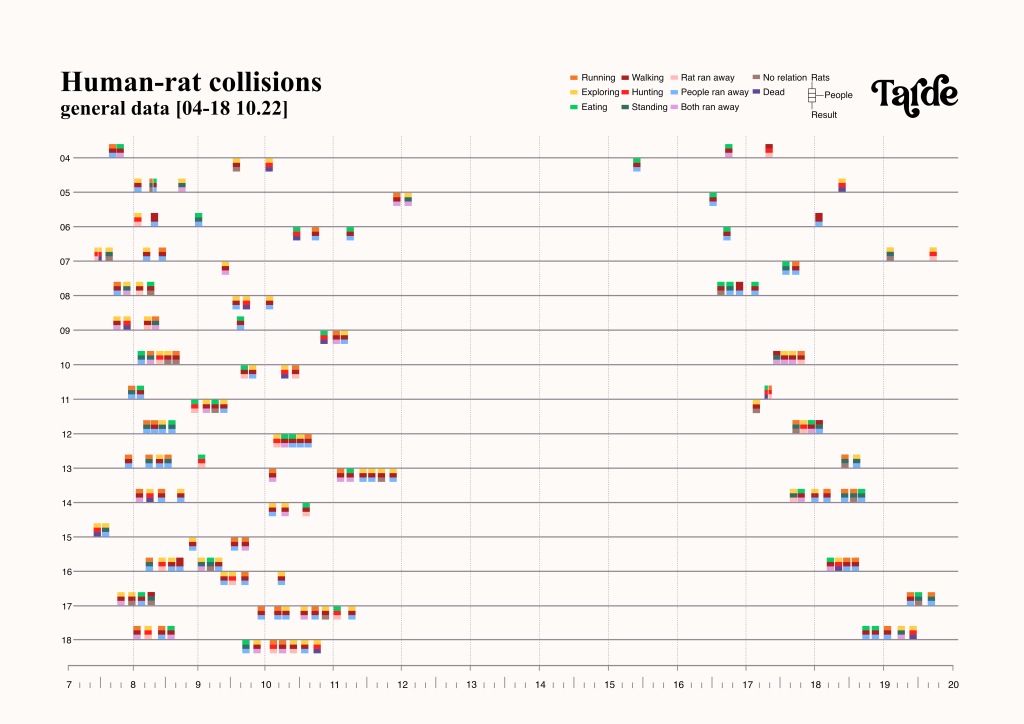

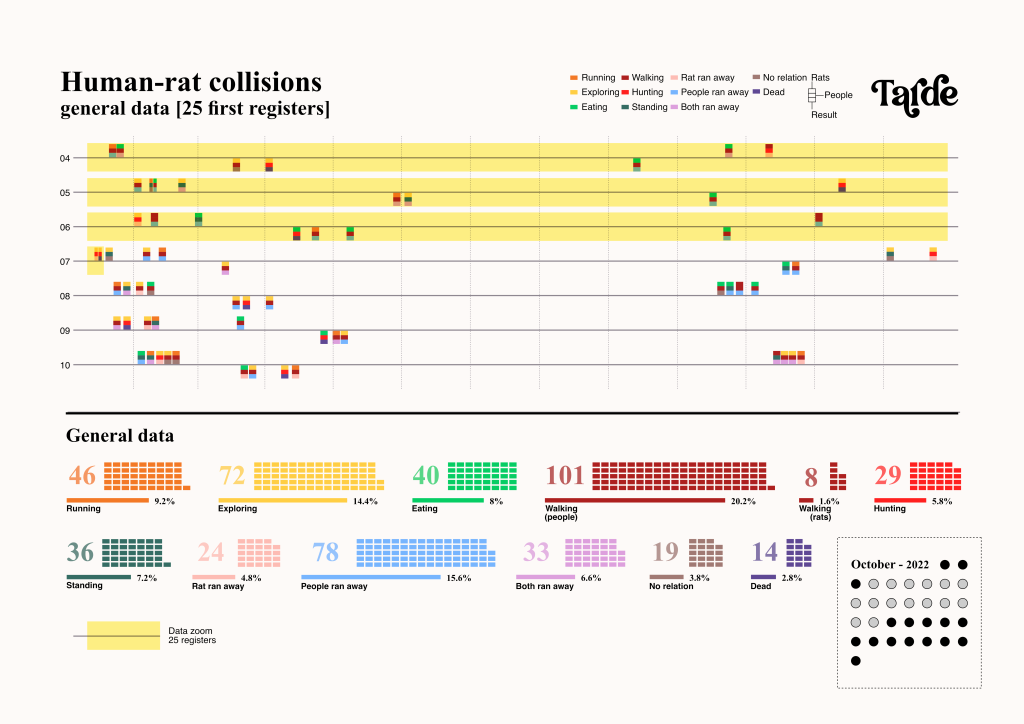

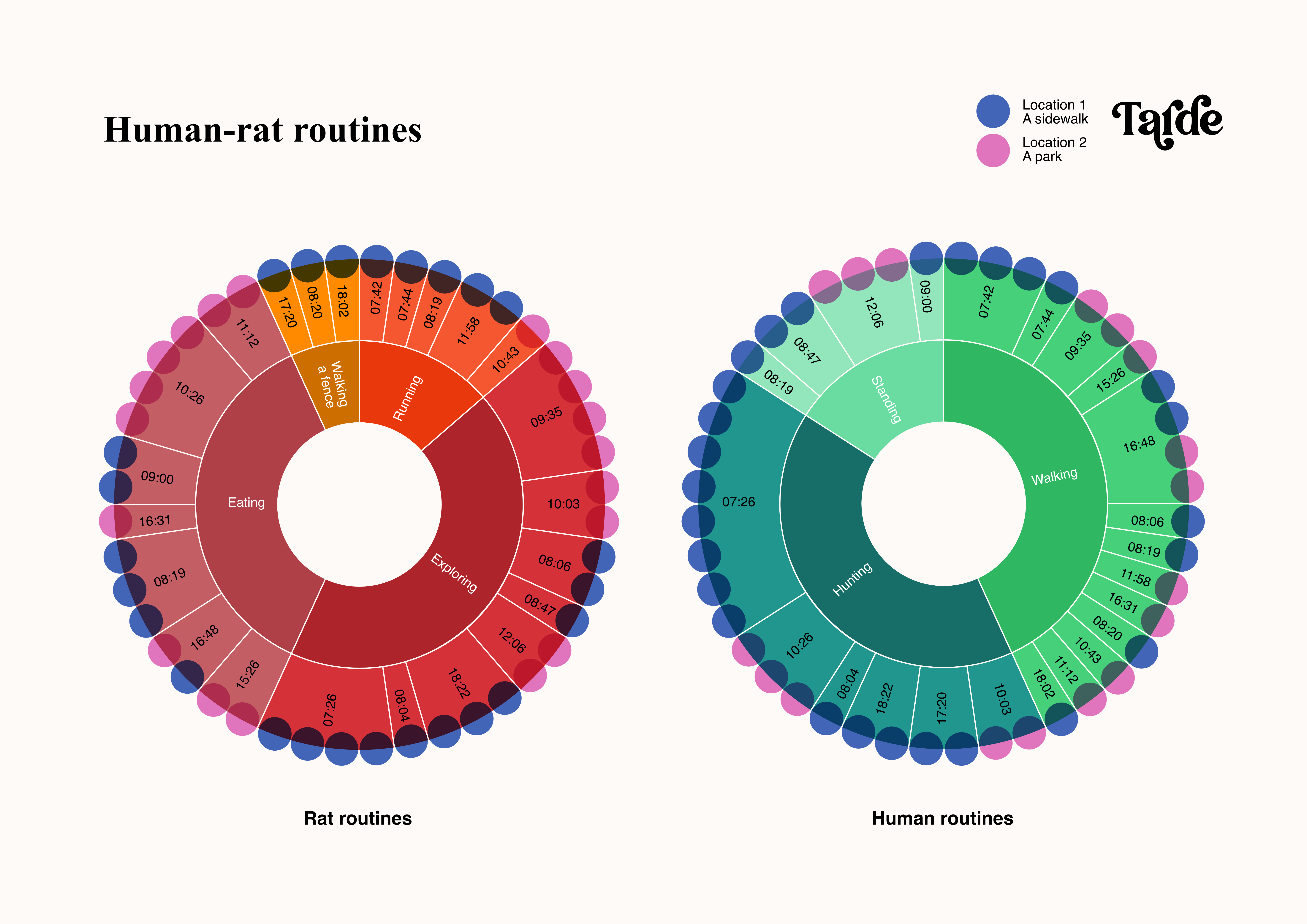

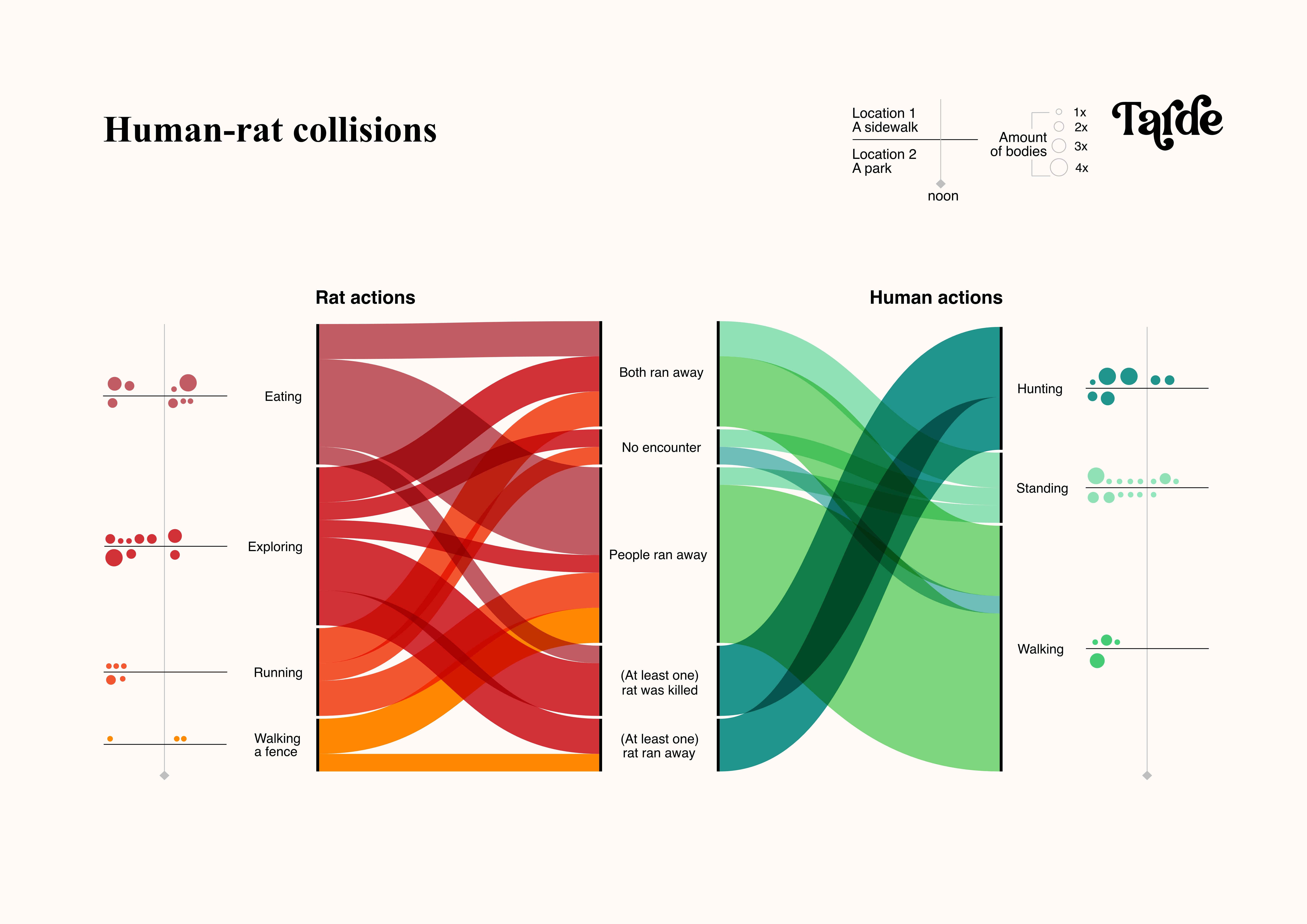

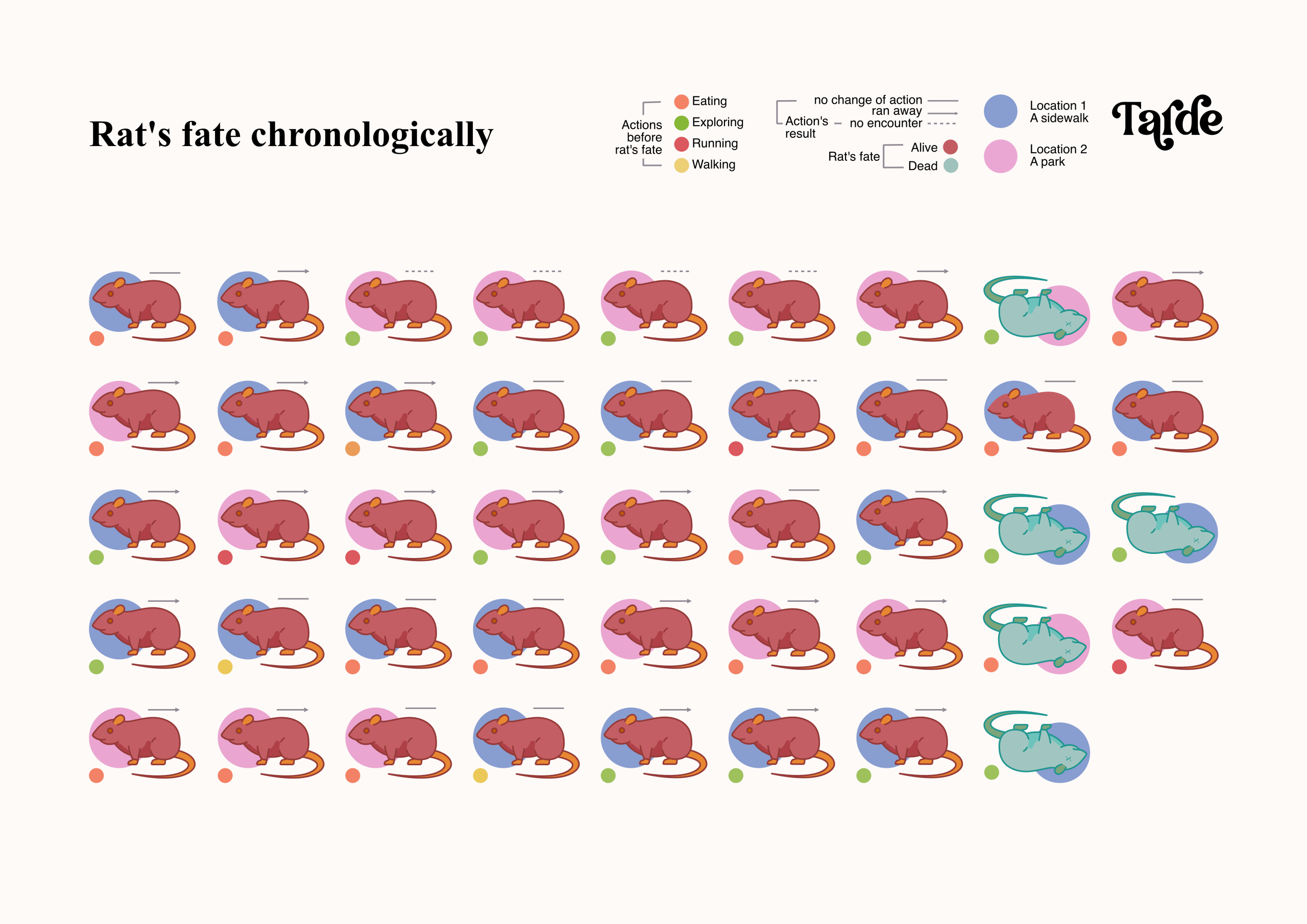

The graphics below are part of two exercises exploring rats’ activities and human-rat interactions in New York City and Medellín, respectively. The first exercise was conducted at almost 40 locations across New York’s Upper West Side between January 2nd and 11th, 2024. The second occurred in 2022 at two different places in Calasanz, a neighborhood in East Medellín. Those observations were made from October 4th to 18th and focused on two groups of rats and their encounters and collisions with people.

New York City

Medellín

Some pictures from New York

The pictures in this gallery were taken during the exercise of documenting rats’ activities and infrastructures around the Upper West Side. They show how rats interact in urban space, not only with human infrastructure such as garbage spots and sidewalks, but also by creating their own.

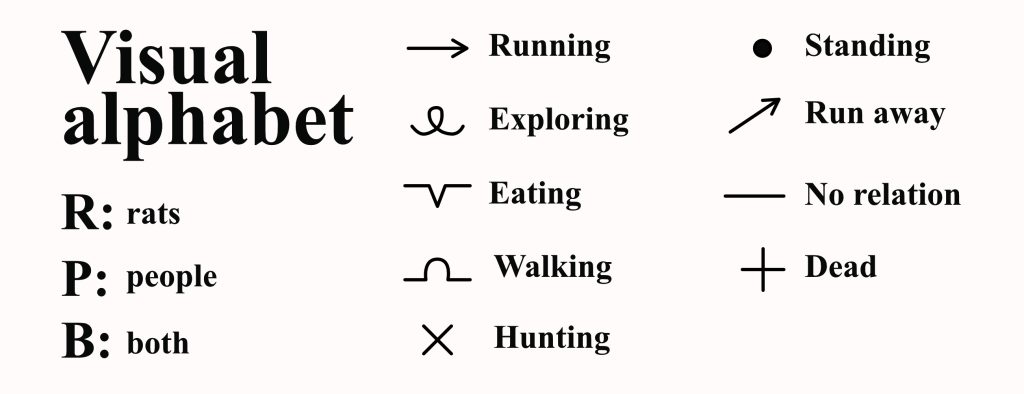

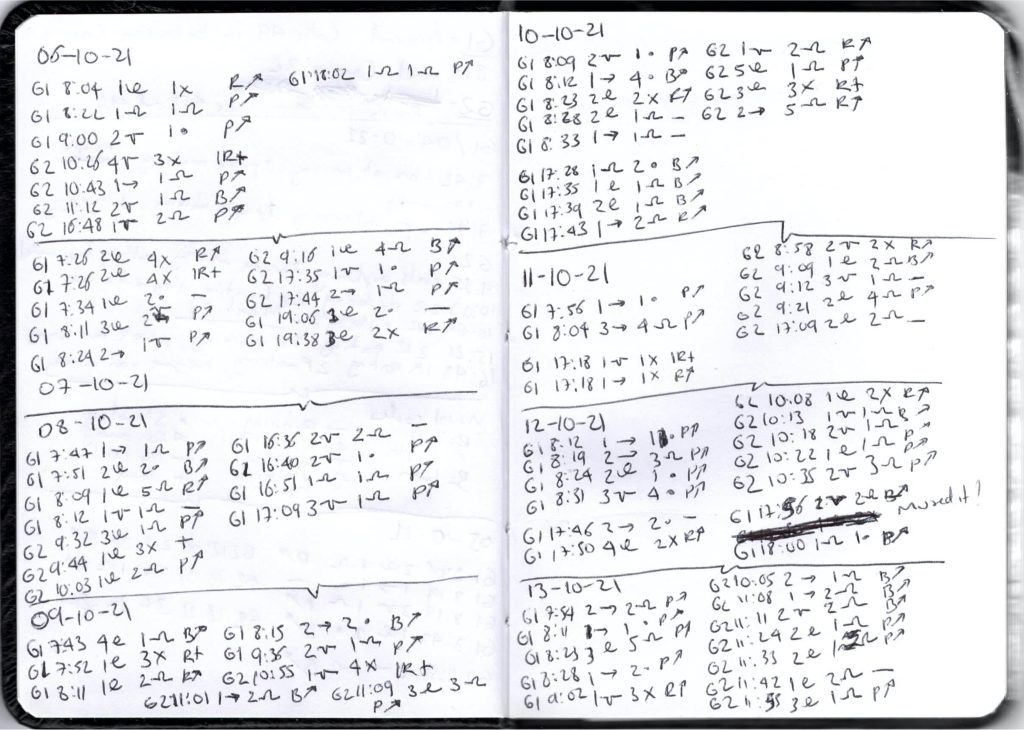

A Watching Rats alphabet

Watching rats in two spots in Medellín posed a methodological challenge that culminated in the development of a specific note-taking system. This system proposed a set of symbols to speed up data collection, as rats were numerous, fast, and elusive. Although it meant a small effort to memorize the characters in the beginning, the fieldnote process went really smoothly once it happened.

Online references

[1] Franklyn, A. (2016). The more-than-human city. The Sociological review 0(0) 1–17. DOI: 10.1111/1467-954X.12396

[2] Arcari, P., Probyn-Rapsey, F., and Singer, F. (2020). Where species don’t meet: Invisibilized animals, urban nature and city limits. Nature and Space 0(0). 1-26. DOI: 10.1177/2514848620939870.

[3] Hovorka, A. (2018). Animal geographies III: Species relations of power. Progress in Human Geography 1–9. DOI: 10.1177/0309132518775837.

[4] Lynteris, C. (ed.) (2019). Framing Animals as Epidemic Villains: Histories of Non-Human Disease Vectors. Palgrave.

[5] Fisell, M. (1999). Imagining Vermin in Early Modern England. History Workshop Journal 47, p. 1.

[6] ibid. p. 2.

[7] Cole, L. (2016). Imperfect Creatures: Vermin, Literature, and the Sciences of Life, 1600-1740. University of Michigan Press. p. 2.

[8] ibid.

[9] ibid.

[10] Edelman, B. (2002). ‘Rats Are People, Too!’ Rat-Human Relations Re-Rated. Anthropology Today 18(3) p. 2.

Handbook references

Medellín

[1] Fisell, M. (1999). Imagining Vermin in Early Modern England. History Workshop Journal 47.

[2] de Bondt, H. and Jaffe, R. (2022) Rats and Sewers: Urban Modernity Beyond the Human. Roadsides, 8, 65-71. https://doi.org/10.26034/roadsides-202200810

[3] Star, SL. (1999). The Ethnography of Infrastructure. American Behavioral Scientist, 43(3), 377-391. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027649921955326.

[4] Larkin, B. (2013). The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure. Annual Review of Anthropology 42(1), 327-343

New York City

[1] Steele, W., Wiesel, I., & Maller, C. (2019). More-than-human cities: Where the wild things are. Geoforum, 106, 411–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.04.007.

[2] Shingne, M. C. (2022). The more-than-human right to the city: A multispecies reevaluation. Journal of Urban Affairs, 44(2), 137–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2020.1734014.

[3] Narayanan, Y. (2017). Street dogs at the intersection of colonialism and informality: ‘Subaltern animism’ as a posthuman critique of Indian cities. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 35(3), 475–494. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775816672860.

[4] Barua, M. (2021). Infrastructure and non-human life: A wider ontology. Progress in Human Geography, 45(6), 1467–1489. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132521991220.

[5] McLuhan, M. (2008). The Gutenberg galaxy: The making of typographic man. University. of Toronto Press.