What was Tarde?

Tarde was an unfinished DIY urban ethnography zine. It evolved into a bimonthly project dedicated to capturing fragments of city life. Each issue focused on unnoticed associations and encounters that were shaping contemporary public spaces. In contrast to academic journals or glossy magazines, Tarde was provisional, handmade, and experimental.

From DIY Culture to Ethnographic Publishing

The project drew inspiration from DIY culture, punk fanzines, guerrilla marketing, and digital self-publishing. Due to this diverse background, the DIY urban ethnography zine explored multiple formats and narratives. Texts, diagrams, images, and even data visualizations appeared alongside each other. Moreover, the zine was curated in collaboration with guest scholars and practitioners to ensure rigor, despite its informal style.

Although Tarde was primarily conceived as self-publishing, it expanded online. Readers around the world could download, print, and redistribute every number under a Creative Commons license. As a result, its distribution was open, collaborative, and accessible.

Minor Ethnographic Stories

At its core, Tarde sought to create minor ethnographic stories. This idea echoed Deleuze and Guattari’s notion of “minor literature.” In other words, Tarde experimented with a language that broke conventions, remained political, and embraced collaboration. Each issue drew attention to elements often overlooked in cities: broken sidewalks, shadows, umbrellas, and other beings that inhabit the urban. Furthermore, it treated these fragments as constitutive parts of urban life, not as waste. Consequently, the zine became a cabinet of infra-ordinary curiosities about more-than-human entanglements.

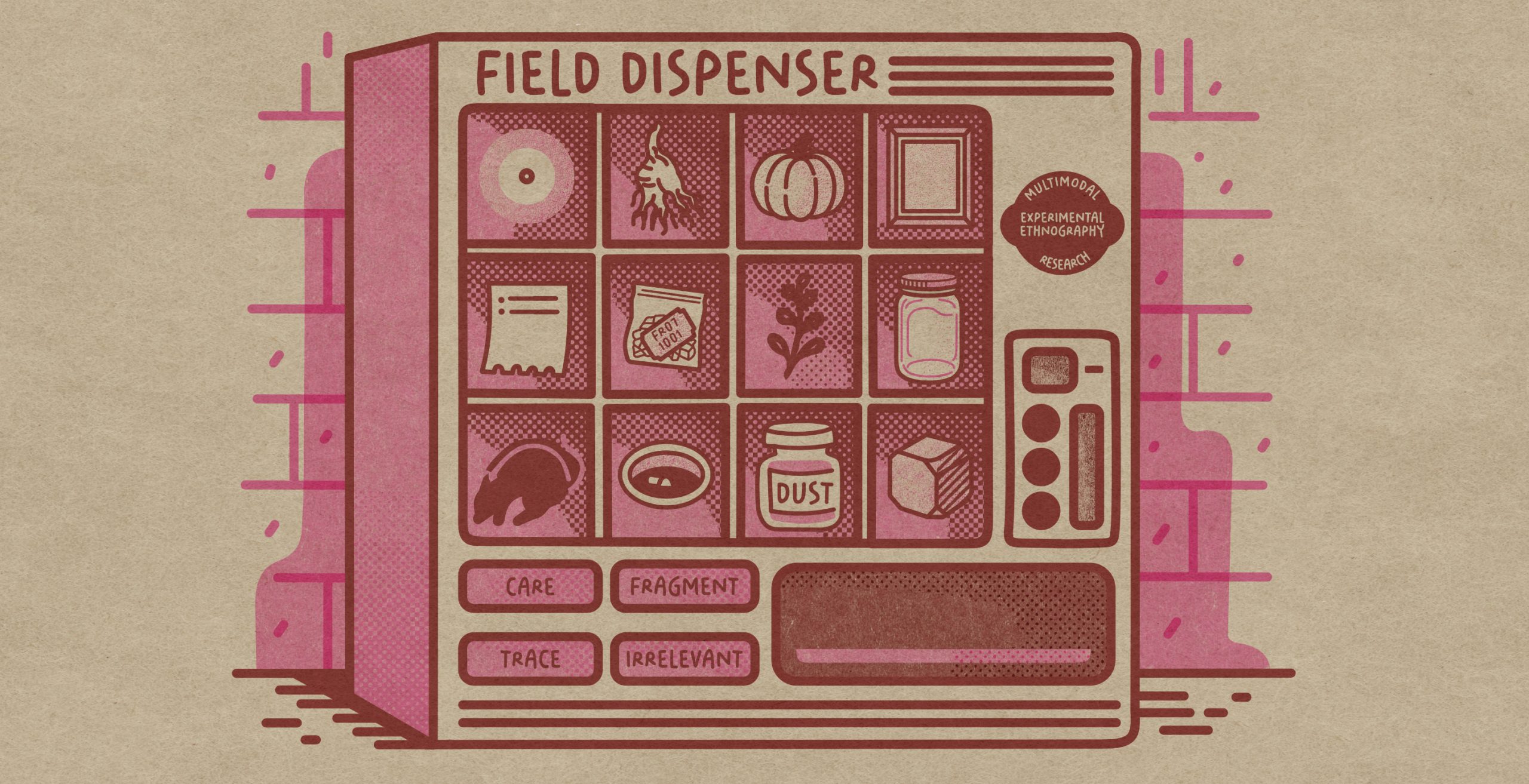

Ethnography as an Inventive Machine

Tarde also proposed ethnography as an inventive machine. For instance, it expanded on Andrea Ballestero and Brit Ross Winthereik’s view of analytic practices as creative devices. Each issue was designed as a testing ground for sensory, multimodal, and experimental methods. The project followed Sarah Pink’s notion of multisensory ethnography. Thus, vision, sound, smell, and touch were treated as interconnected rather than separate. It also drew on Celia Lury and Nina Wakeford’s ideas about methodological invention. Therefore, every edition functioned as a material artifact, a device to generate insights in new ways.

Why the Name Tarde?

The name honored Gabriel Tarde (1843–1904), a French sociologist focused on small interactions and singularities. His ideas lost prominence to Durkheim’s macro-sociology but influenced Deleuze, Latour, and the development of assemblage theory. In line with this legacy, Tarde the zine emphasized everyday encounters and minimal details that accumulate into complex urban networks.

An Experiment That Lives On

Throughout its run, Tarde resisted large publishing companies and academic gatekeeping. Instead, it created a hybrid artifact: a combination of printed and digital, collectible and shareable. Issues circulated through cafés, libraries, and urban corners. Ultimately, the project came to an end, but its traces remain. Together, the issues form a cabinet of unfinished fragments. As a result, they continue to invite readers to imagine other ways of doing and communicating ethnography.