Materialtone began as a side–experiment in the middle of my doctoral fieldwork in New York City. I was spending long days around Times Square, trying to understand this overloaded place through an STS-inspired urban ethnography: infrastructures, screens, flows of people, maintenance work, security routines.

At some point I realized that, no matter where I looked, color and texture kept pulling me back in. Times Square is a jungle of surfaces: red glass, grimy concrete, brushed metal, plastic barriers, glowing billboards, and chewing-gum stains. I started wondering:

- What if I tried to exhaust Times Square chromatically?

- Could I decompose the place into a collection of material swatches?

- What kind of ethnography would emerge if I treated the city like a palette?

From Pantone to Materialtone

Out of these questions came the first formulation of Materialtone, written in the appendix to my dissertation as one of several speculative artifacts from the Artefaktenatelier—a workshop for experimenting with multimodal ethnography of urban places.

Back then I described it, very simply, as:

Materialtone. A set of cards.

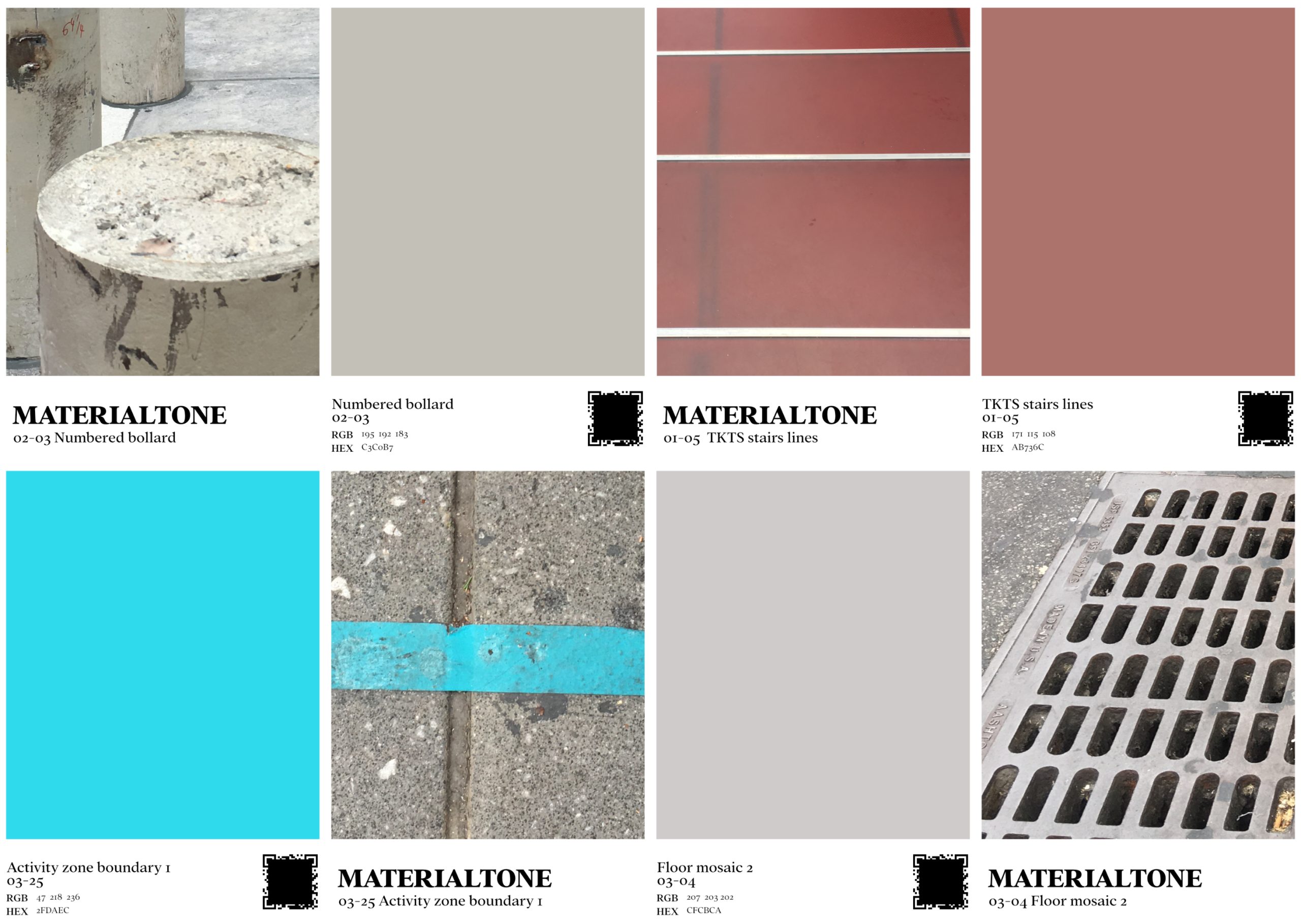

A collection of cards, each displaying a picture of a single material composing Times Square. The cards would be labeled and classified, offering another way to approach the square. Inspired by the Pantone color system, the idea was to exhaust the place by decomposing it into the many elements one can find there.

The plan was to walk, photograph tiny pieces of Times Square (a stair tread, a barrier, a stain), crop each image, pull out a dominant color, and design cards that looked a bit like Pantone swatches—but rooted in specific urban fragments.

I didn’t yet have the language of “urban STS” or “multimodal ethnography as broth and seasoning.” Still, the intuition was there: if infrastructures are held together by standards, colors, textures, and repairs, then perhaps one could study them through a palette.

Barcelona: minimal details, everyday urbanism

A few years later, in Barcelona, the experiment resurfaced. This time the focus shifted away from the spectacle of Times Square toward the minimal and seemingly irrelevant details that compose everyday urban life: curb edges, painted bike lanes, worn tiles, improvised fixes.

I began producing new cards, now more attuned to:

- accessible ramps and tactile pavings,

- improvised signage and taped repairs,

- the soft borders between tourist infrastructures and ordinary neighborhoods.

Barcelona helped me see Materialtone not only as a visual game but also as a way to track how regulations, accessibility standards, and tourist economies materialize on the ground. The cards started to feel less like an appendix project and more like a portable method.

Magdeburg: decay, functionality, and the palette of maintenance

In Magdeburg, the experiment took another turn. I adopted a more explicitly artistic and atmospheric gaze, seeking common ground between decay and functionality: bollards filled with trash, stained pavements, scuffed markings, chipped paint.

Here the palette darkened. Browns, greys, and washed-out yellows spoke of:

- infrastructures that still work but are clearly tired,

- spaces where cleaning and repair labor is unevenly distributed,

- improvisations that keep things running with minimal resources.

Magdeburg made “dirty floors,” abandoned buildings, and improvised repairs central to Materialtone. The cards were not just about neat standards; they became a way of reading wear and neglect as diagnostic colors of the city.

Bogotá: fragments and specimenography

Now, in Bogotá, Materialtone returns in dialogue with my ongoing work on fragments, residues, and specimenography. I am interested in how urban spaces come apart: chipped curbs, layered paints, patched surfaces, provisional markings. The cards become chromatic specimens of these fragmented infrastructures.

Bogotá is where I start explicitly treating Materialtone as an urban STS method with multimodal ethnography as its methodological partner:

- Urban STS provides the broth: it keeps me focused on infrastructures, standards, maintenance, accessibility, governance.

- Multimodal ethnography provides the seasoning: walking, photographing, cropping, sampling colors, designing cards, and attaching QR codes become a chain of translations through which these issues become sensible and shareable.

From experiment to method

Across New York, Barcelona, Magdeburg, and Bogotá, Materialtone has slowly evolved from an appendix idea into a more coherent approach to studying cities “from below,” through the surfaces we step on and lean against.

In its current form, Materialtone treats each card as:

- a color standard and script (what this tone asks bodies to do),

- a surface interface (where feet, wheels, liquids, and rules meet),

- a technology of coordination (linking actors, brands, and regulations),

- and a diagnostic of decay and repair (how infrastructures age, fail, or are patched).

This introductory post is the starting point for a new phase of the project within my Visual Ethnography work. Future entries will:

- present selected Materialtone cards from different cities and urban places,

- unpack the socio-technical stories behind each color/texture,

- and experiment with ways of using these palettes in teaching, collaborative walks, and other multimodal formats.

Materialtone began as a question scribbled in a dissertation appendix. It now returns as a method to think with: a way of asking how cities are held together chromatically and texturally—and what becomes visible when we learn to read the urban world as a shifting, fragmentary color chart.