From The Atelier Series

Emden, 2023

Tarde began as a small experiment—an afternoon of folding and cutting paper, a game of formats. However, it soon evolved into something else: a means to rethink how ethnography could be practiced and shared (Marcus 2013; Schneider & Wright 2010). I had been reflecting on the minimal and often overlooked details that give texture to urban life, and I wanted to find a form that could hold those fragments without exhausting them (Stewart 2007; Ingold 2013).

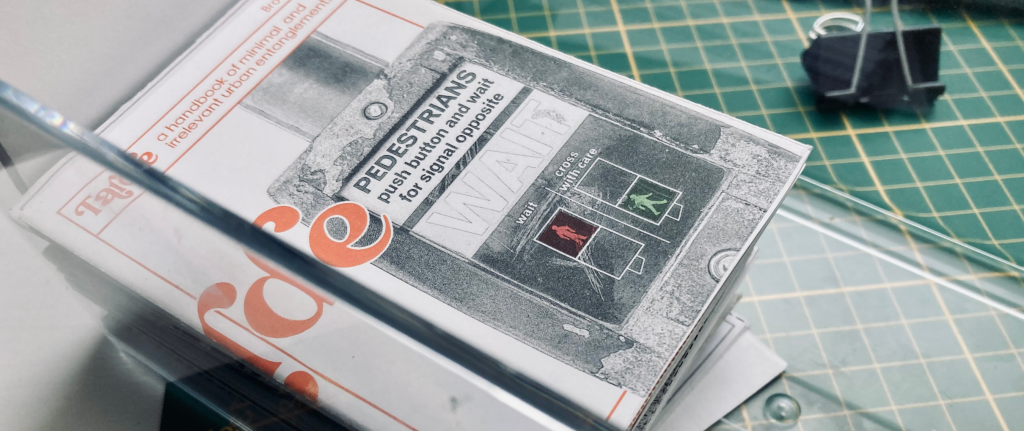

In Emden, I was surrounded by cutting mats, rulers, cutters, and printers. The studio became both a laboratory and a press. I printed, folded, and assembled zines that treated fieldwork fragments as material evidence—pages as specimens (Lury & Wakeford 2012; Drazin & Küchler 2015). Tarde was never meant to explain; it was meant to show how ethnography could be a tactile, distributable, and public act (Pink 2015; Collins, Durington & Gill 2017).

Each issue was an experiment in method: one focused on infrastructural glitches, another on animals killed by neglect, and another on the shadows and tactics for studying them. The zine’s form mirrored its content—compact, folded, quietly resistant to academic scale. It proposed that the smallest gestures of city life could become ethnographic artifacts if one paid enough attention (Ingold 2018; Puig de la Bellacasa 2017).

The process of making Tarde reconnected me to design as a way of thinking. Layout became a method, typography a form of argument, and color a way of tracing relations (Gunn, Otto & Smith 2013; Myers 2015). Through risograph printing, I rediscovered imperfection as aesthetic and epistemic value—the slight misalignments and ink saturations that speak of manual care and situated making (Manning 2016; Taussig 2011).

This process blurred the boundaries between ethnography, art, and publishing. Tarde was an open-access ethnography, intended for circulation both within and outside academia. Its low-cost, reproducible format was a political decision—a commitment to accessibility and shared curiosity (Kelty 2008; Haraway 2016). Each issue could be downloaded, printed, and folded by anyone, anywhere.

I also saw Tarde as a pedagogical tool. In my Urban Mapping course, I began using zine-making to teach students how to observe differently—to treat layout as an argument, scale as a method, and folding as a reflection (Lupton 2014; Pink et al. 2016). The exercise demonstrated that ethnographic thinking thrives in dynamic, mobile, and tangible formats (Rabinow et al. 2008).

In retrospect, Tarde consolidated what the Artefaktenatelier had always implied: that ethnography is not just about writing but about crafting. It is an act of making visible the minimal, the irrelevant, the ordinary—those fragments that hold the density of shared worlds. Through Tarde, the Ethnographic Atelier found one of its simplest and most enduring forms: the printed fold.

References

- Collins, Samuel, Matthew Durington, and Harjant Gill. 2017. Networked Anthropology: A Primer for Ethnographers. Routledge.

- Drazin, Adam, and Susanne Küchler. 2015. The Social Life of Materials: Studies in Materials and Society.Bloomsbury.

- Gunn, Wendy, Ton Otto, and Rachel Charlotte Smith, eds. 2013. Design Anthropology: Theory and Practice.Bloomsbury.

- Haraway, Donna J. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press.

- Ingold, Tim. 2013. Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. Routledge.

- Ingold, Tim. 2018. Anthropology: Why It Matters. Polity Press.

- Kelty, Christopher M. 2008. Two Bits: The Cultural Significance of Free Software. Duke University Press.

- Lupton, Ellen. 2014. Graphic Design: The New Basics. 2nd ed. Princeton Architectural Press.

- Lury, Celia, and Nina Wakeford, eds. 2012. Inventive Methods: The Happening of the Social. Routledge.

- Manning, Erin. 2016. The Minor Gesture. Duke University Press.

- Marcus, George E. 2013. “Experimental Forms for the Expression of Norms in the Ethnography of the Contemporary.” Hau: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 3(2): 197–217.

- Myers, Natasha. 2015. Rendering Life Molecular: Models, Modelers, and Excitable Matter. Duke University Press.

- Pink, Sarah. 2015. Doing Sensory Ethnography. 2nd ed. Sage.

- Pink, Sarah, Kerstin Leder Mackley, Roxana Morosanu, Vaike Fors, and Val Mitchell. 2016. Making Homes: Ethnography and Design. Bloomsbury.

- Puig de la Bellacasa, María. 2017. Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More-Than-Human Worlds. University of Minnesota Press.

- Rabinow, Paul, George E. Marcus, James D. Faubion, and Tobias Rees. 2008. Designs for an Anthropology of the Contemporary. Duke University Press.

- Schneider, Arnd, and Christopher Wright, eds. 2010. Between Art and Anthropology: Contemporary Ethnographic Practice. Berg.

- Stewart, Kathleen. 2007. Ordinary Affects. Duke University Press.

- Taussig, Michael. 2011. I Swear I Saw This: Drawings in Fieldwork Notebooks, Namely My Own. University of Chicago Press.