From The Atelier Series

Medellín, 2021

In 2021, I returned to Medellín, my hometown, for the first time since finishing my PhD. I stayed for two months, walking the city’s streets with a different gaze—one shaped by years of thinking about artifacts, fragments, and infrastructures. This time, I wasn’t looking for order but for the interruptions, the temporary repairs, the improvisations that keep a city moving despite its cracks (Larkin 2013; Graham & Thrift 2007).

I called them glitch infrastructures—sidewalks that, although broken, still worked. Holes filled with wood planks, tiles replaced with improvised cement patches, or stones shifted just enough to let water flow. Each repair carried a small story of adaptation and survival (Denis & Pontille 2015). These glitches revealed an urban intelligence distributed across materials, workers, and passers-by: a choreography of care that kept things functioning, if only barely (Jackson 2014; Puig de la Bellacasa 2017).

This work became part of the Tarde series, an attempt to document and think with failure. Rather than treating brokenness as a deficit, I approached it as a method—a way to read the city through its temporary fixes and unstable continuities (Halberstam 2011; Graham & McFarlane 2014). Glitch Infrastructures was a way of asking what remains operational when systems fail, and how repair can exist without perfection (Henke 1999; Jackson 2014).

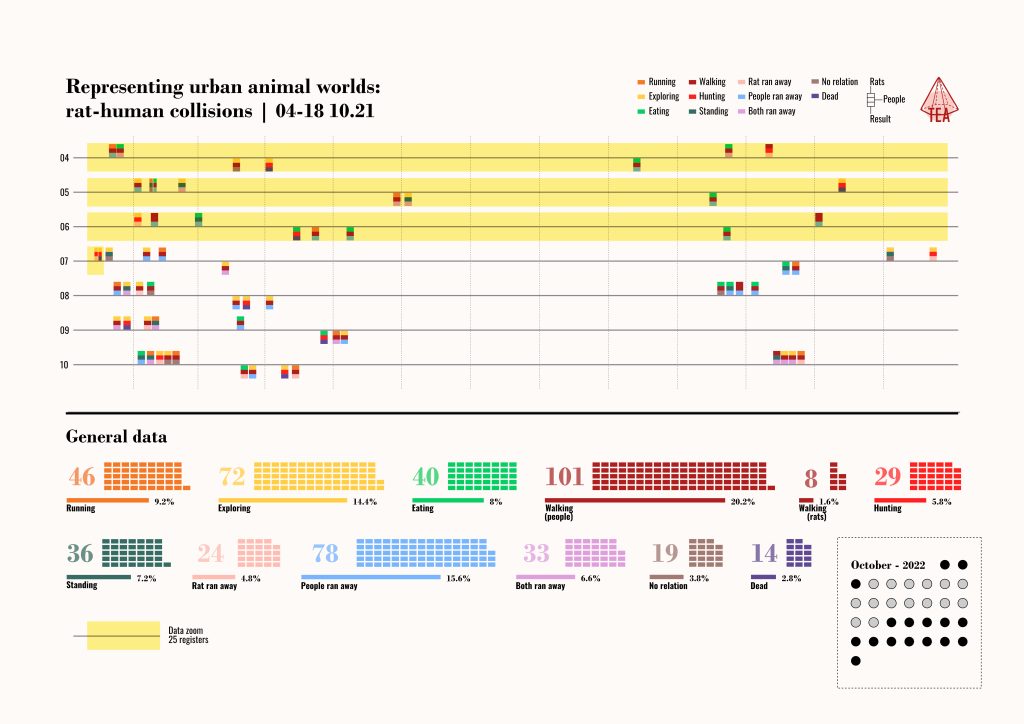

At the same time, another theme began to take shape: the presence of rats in the city. These animals moved through sewers, markets, and alleys, co-producing the urban with humans in hidden ways (Despret 2016; Ogden, Hall & Tanita 2013). I followed them in field notes, conversations, and drawings, observing how their trails intersected with the infrastructures of waste, food, and shelter (Keck 2020; Hitchings 2012). The rat became an ethnographic guide, an uninvited collaborator who revealed the porousness of human spaces (Tsing 2015).

This encounter—between rats and people—opened new methodological and ethical questions. How do we write about beings that are simultaneously abjected and infrastructural (Kirksey 2014; Govindrajan 2018)? How do we account for the labor of those whose presence sustains the city precisely by being denied? The rat-human relation became a conceptual hinge, a prototype for my later project on multispecies encounters in Berlin.

In retrospect, Medellín felt like both a return and an experiment. It was a city of layered memories and renewed methods—a place where the field became both literal and diagrammatic. My walks, photos, and sketches were part of a growing visual notebook that continued to merge ethnography and design, documenting glitches, encounters, and the aesthetic of the almost-broken (Stewart 2007; Pink 2015).

Back in Europe, I realized how much of my later work had already been rehearsed there, in those streets. Glitch Infrastructures and the rat studies taught me to see the city as a multispecies assemblage of improvisations (Bennett 2010; Haraway 2016). Medellín was not just a site but a studio of failure and resilience, where ethnography itself learned to walk unevenly—and still work.

References

- Bennett, Jane. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Duke University Press.

- Denis, Jérôme, and David Pontille. 2015. “Material Ordering and the Care of Things.” Science, Technology, & Human Values 40(3): 338–367.

- Despret, Vinciane. 2016. What Would Animals Say If We Asked the Right Questions? University of Minnesota Press.

- Govindrajan, Radhika. 2018. Animal Intimacies: Interspecies Relatedness in India’s Central Himalayas.University of Chicago Press.

- Graham, Stephen, and Colin McFarlane, eds. 2014. Infrastructural Lives: Urban Infrastructure in Context.Routledge.

- Graham, Stephen, and Nigel Thrift. 2007. “Out of Order: Understanding Repair and Maintenance.” Theory, Culture & Society 24(3): 1–25.

- Halberstam, Jack. 2011. The Queer Art of Failure. Duke University Press.

- Haraway, Donna J. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press.

- Henke, Christopher R. 1999. “The Mechanics of Workplace Order: Toward a Sociology of Repair.” Berkeley Journal of Sociology 44: 55–81.

- Hitchings, Russell. 2012. “People, Plants and Performance: On Actor Network Theory and the Material Pleasures of the Private Garden.” Social & Cultural Geography 4(1): 99–114.

- Jackson, Steven J. 2014. “Rethinking Repair.” In Media Technologies: Essays on Communication, Materiality, and Society, edited by Tarleton Gillespie, Pablo Boczkowski, and Kirsten Foot, 221–239. MIT Press.

- Keck, Frédéric. 2020. Avian Reservoirs: Virus Hunters and Birdwatchers in Chinese Sentinel Posts. Duke University Press.

- Kirksey, Eben, ed. 2014. The Multispecies Salon. Duke University Press.

- Larkin, Brian. 2013. “The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure.” Annual Review of Anthropology 42: 327–343.

- Ogden, Laura, Billy Hall, and Kimiko Tanita. 2013. “Animals, Plants, and People: Extending Entanglements in the Anthropocene.” Environment and Society: Advances in Research 4(1): 35–53.

- Pink, Sarah. 2015. Doing Sensory Ethnography. 2nd ed. Sage.

- Puig de la Bellacasa, María. 2017. Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More-Than-Human Worlds. University of Minnesota Press.

- Stewart, Kathleen. 2007. Ordinary Affects. Duke University Press.

- Tsing, Anna. 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins.Princeton University Press.