From The Atelier Series

Lübeck, 2021

By 2021, I was no longer in Munich. I had moved north, to Lübeck (after a stopover in Berlin) — a quieter and more introspective place. After years of fieldwork, experiments, and travel, Lübeck became the studio I had always imagined. It was there—between canals, wooden floors, and slow winter light—that the Artefaktenatelier turned from a conceptual draft into an ethnographic method (Lury & Wakeford 2012; Marcus 2013).

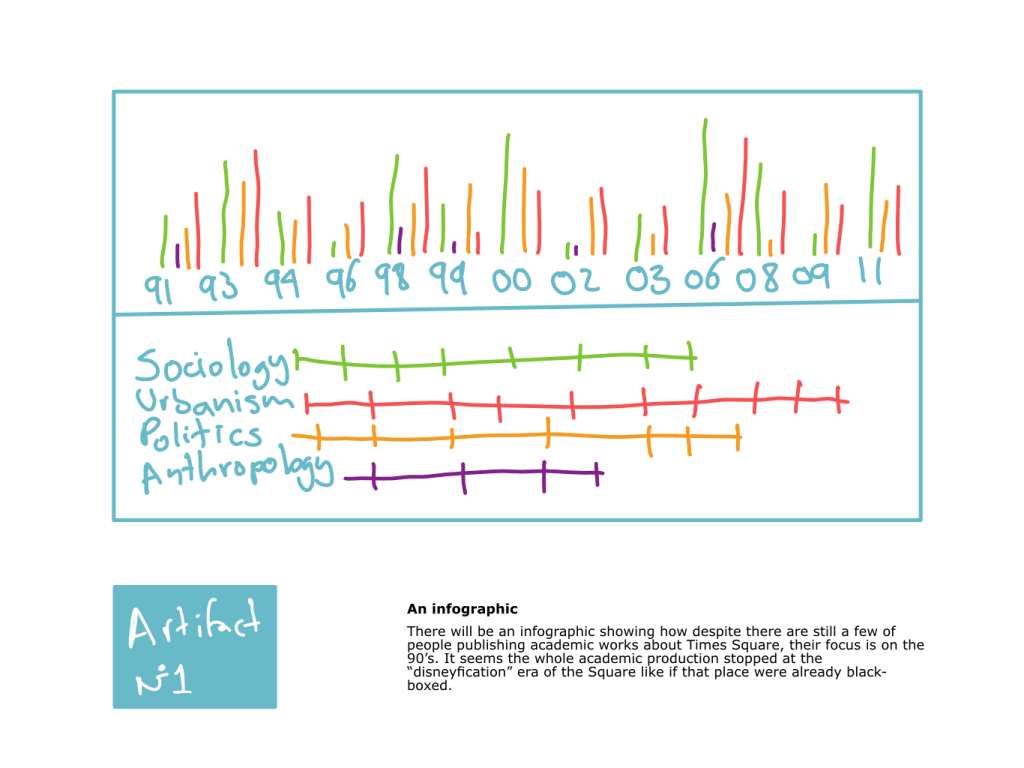

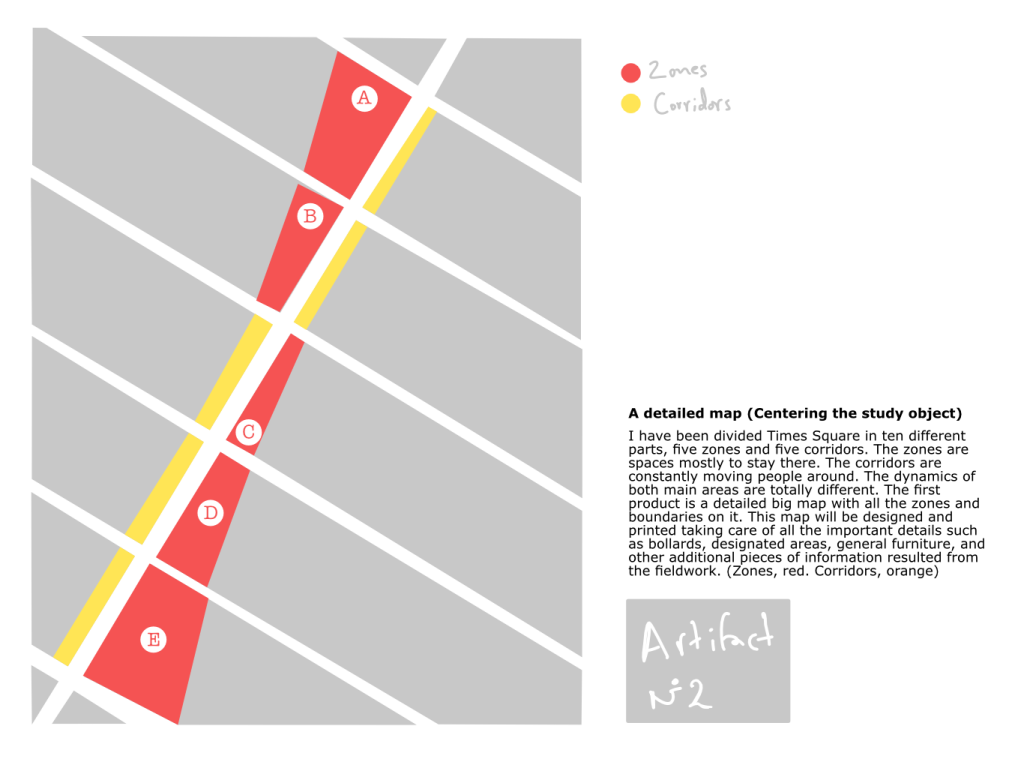

The field was still present, but now through its traces: fieldnotes, images, and maps from Times Square. That chaotic plaza had been both my site and my collaborator (Rabinow et al. 2008). In Lübeck, I began to assemble what I had learned—about attention, sensory overload, and the impossibility of linear ethnography (Stewart 2007; Manning 2016). What emerged was a practice of writing with fragments, of diagramming instead of describing (Ingold 2011; Latour 1990).

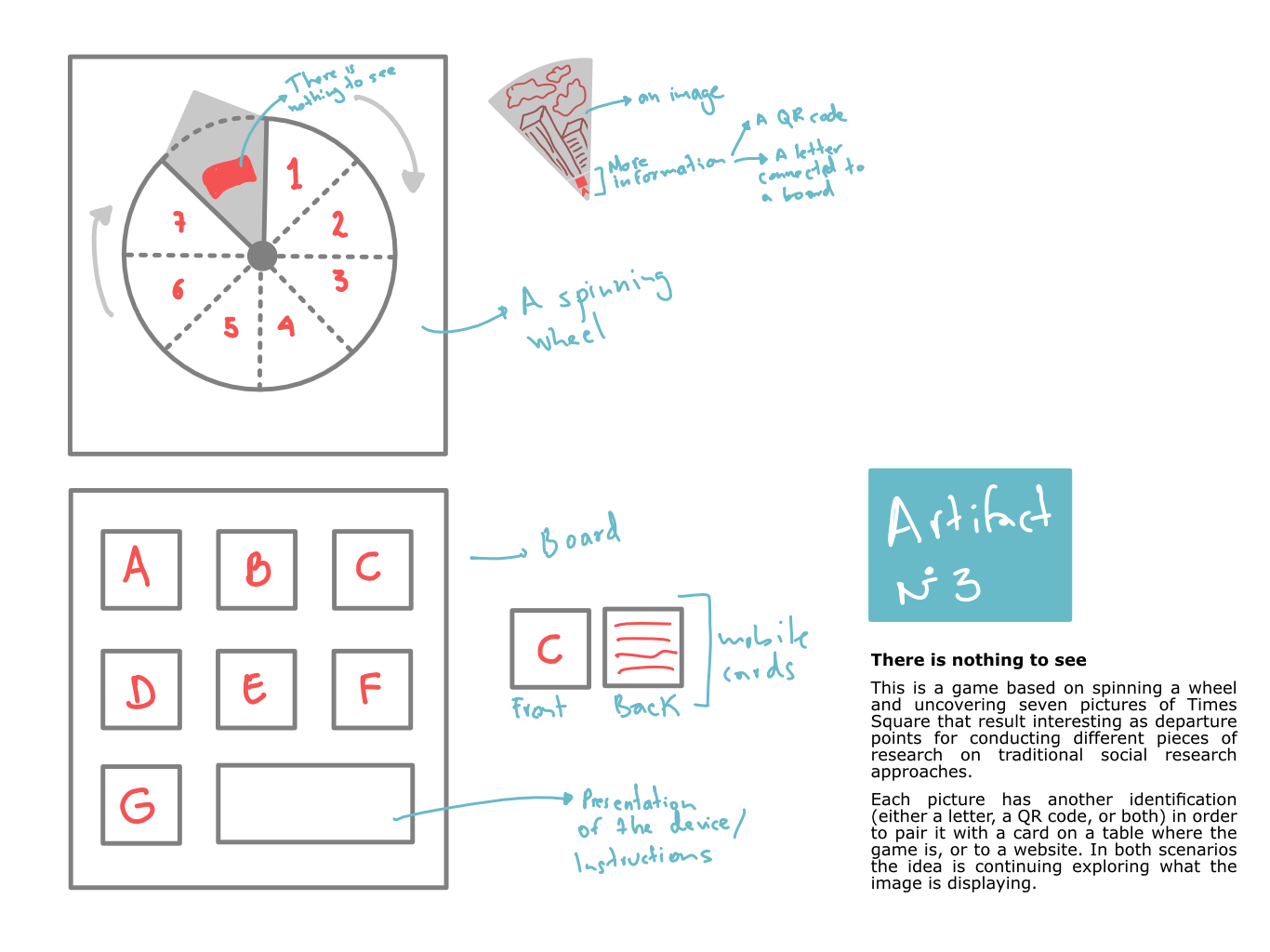

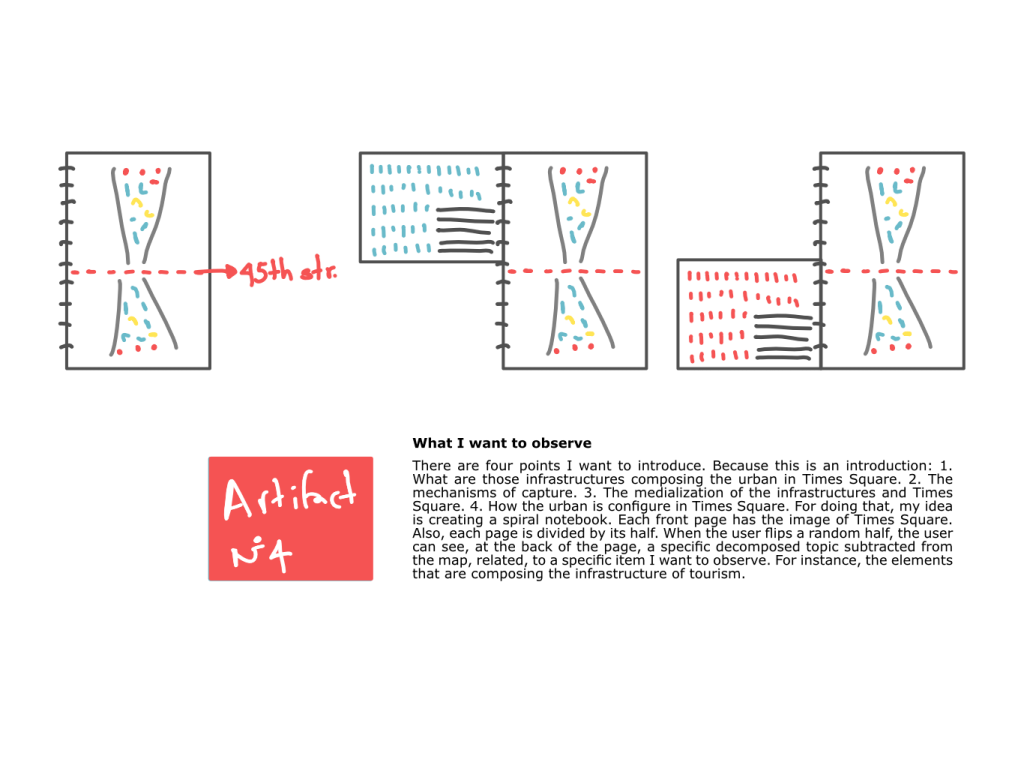

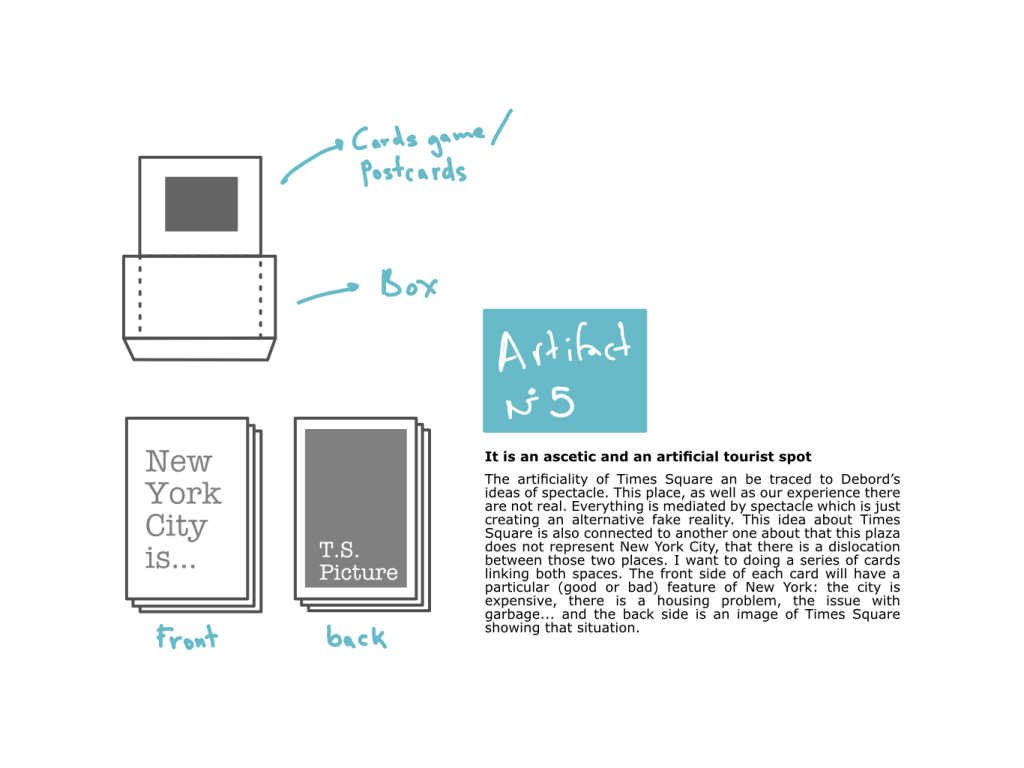

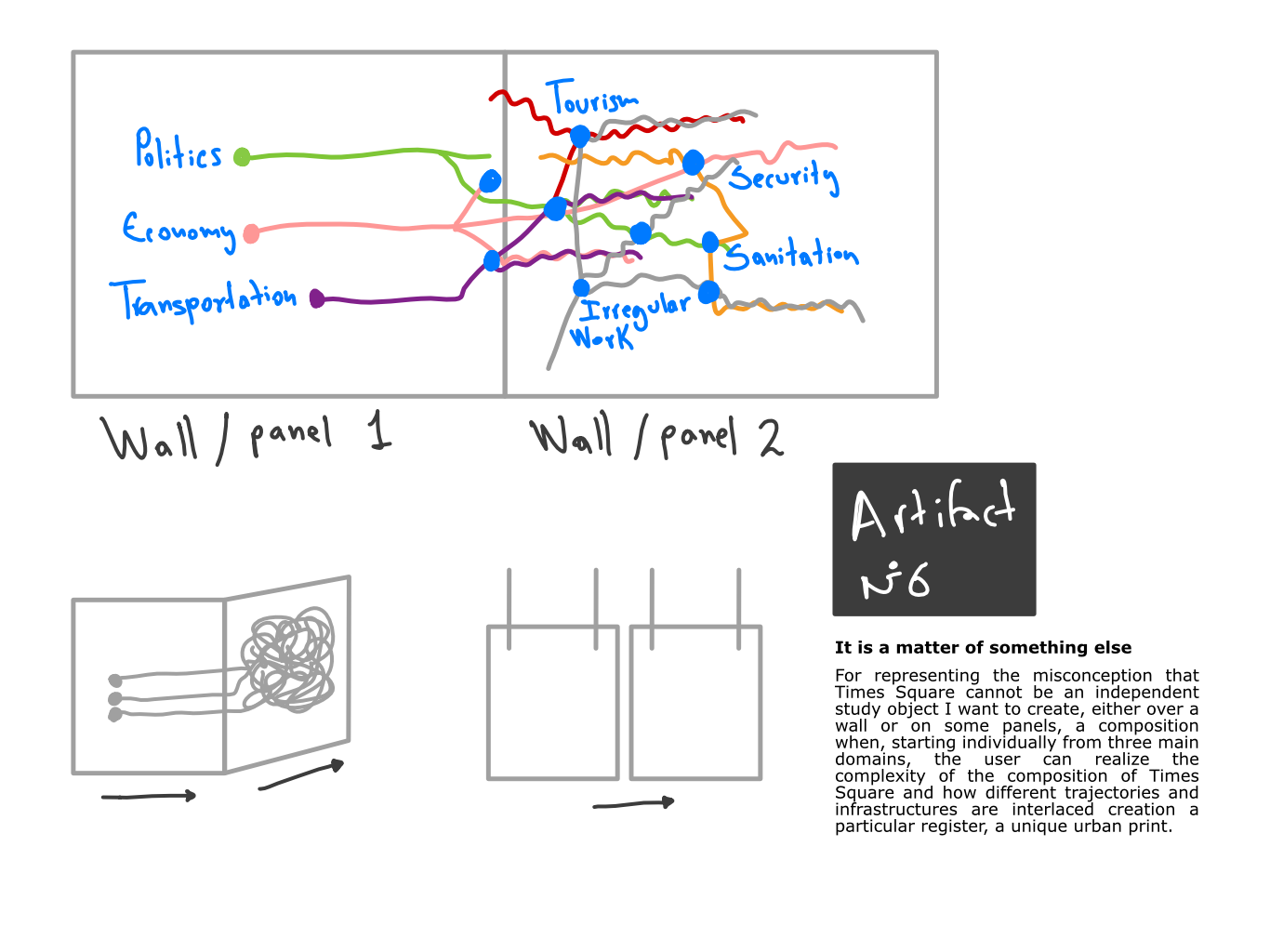

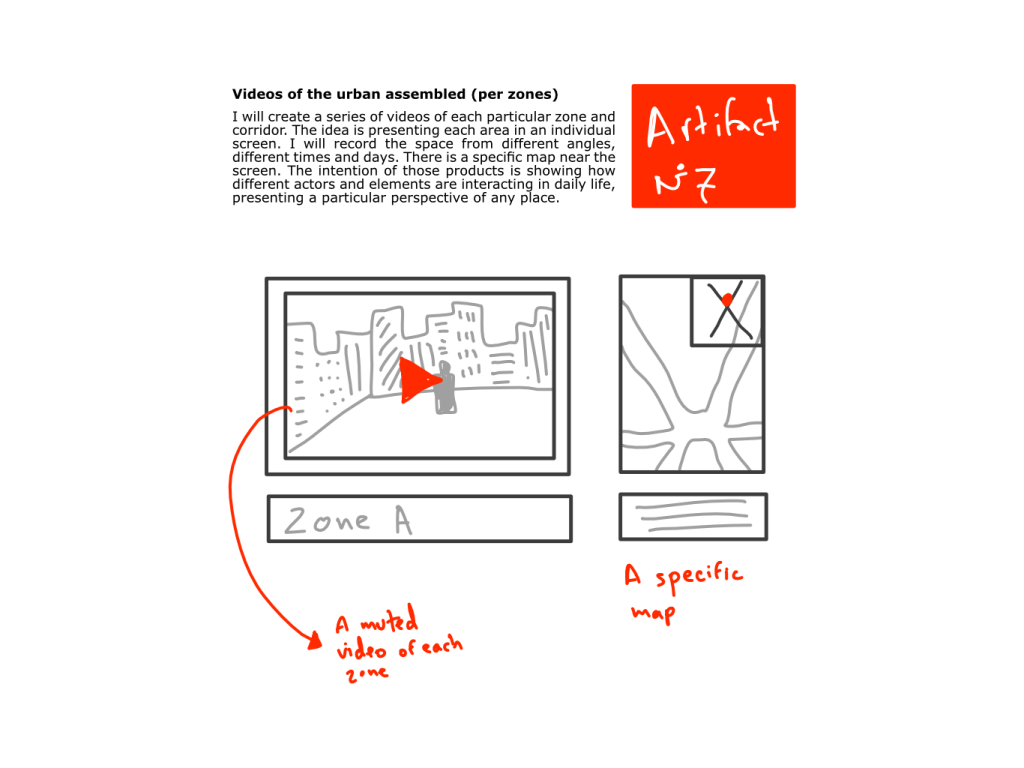

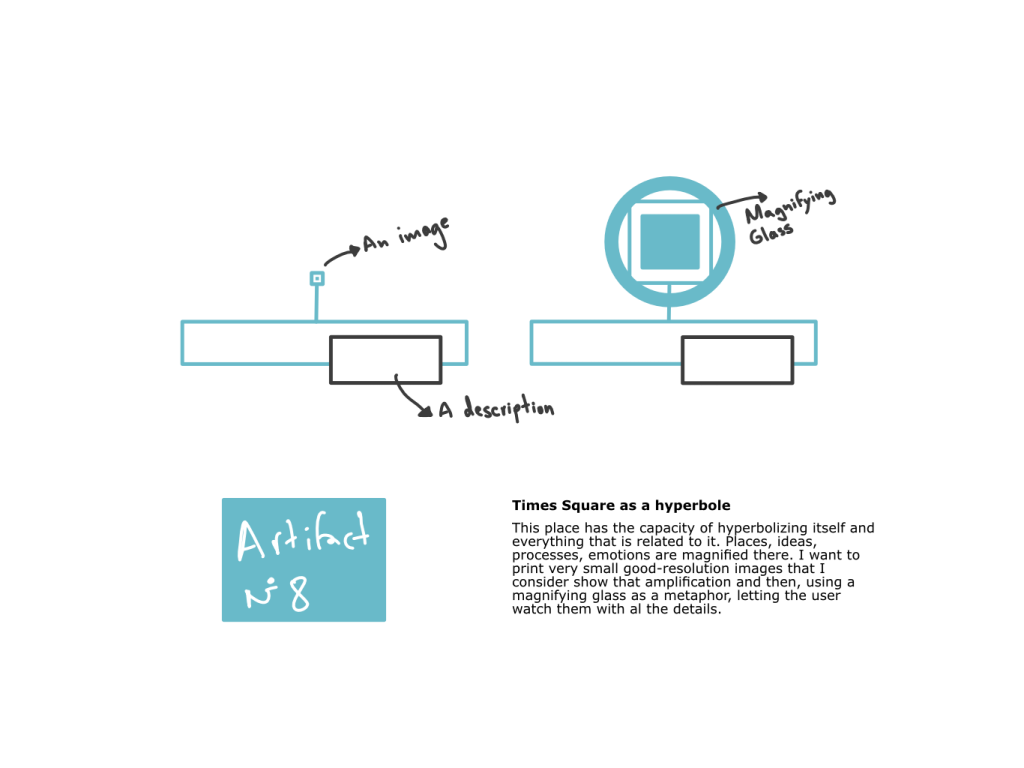

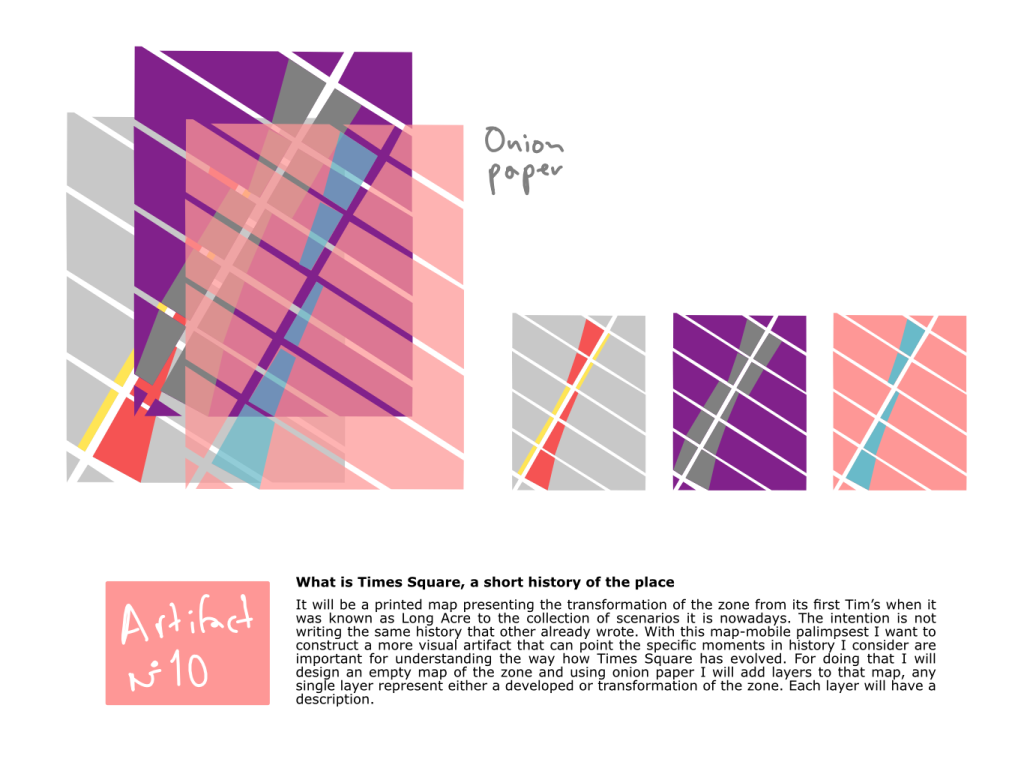

The Artefaktenatelier evolved into a framework for doing and thinking at once. Each chapter of my dissertation became an artifact —an experiment with form: diagrams, sequences, and speculative maps (Schneider & Wright 2010; Drazin & Küchler 2015). I realized that the urban was not only my subject but my method. The flows, screens, and intensities of Times Square seeped into the very structure of the text, turning it into a labyrinth—a book that could be navigated rather than read (de Certeau 1984; Massumi 2011).

In Lübeck, the diagram from Munich returned. I pinned it to the wall and began tracing lines between theory, fieldwork, and form (Latour 2008; Rheinberger 1997). The studio had become portable: part laptop, part notebook, part reflection. This was where I understood that the Artefaktenatelier was never meant to be a single place, but a mode of working—a way of transforming ethnographic uncertainty into artefactual clarity (Suchman 2011; Myers 2015).

The process of writing was inseparable from the act of designing. I built visual sequences to test arguments, mapped movements of bodies and screens, and transformed field encounters into epistemological devices (Gunn, Otto & Smith 2013; Law 2004). These artifacts were not illustrations but thinking tools—extensions of ethnographic reasoning that let form and theory coevolve (Ingold 2013; Manning & Massumi 2014).

Looking back, Lübeck was not a break from fieldwork but its metamorphosis. The Artefaktenatelier had shifted from idea to practice, from question to method. It became the scaffolding for a multimodal, diagrammatic, and affectively grounded ethnography (Collins, Durington & Gill 2017; Pink 2015). Through systematization, I was also reconfiguring what counts as ethnographic knowledge (Ingold 2018).

When I finally printed the dissertation, I felt it was less a closure and more a prototype—a labyrinthine artifact born from Times Square but assembled in Lübeck. The Artefaktenatelier had proven itself to be a space for thinking through fragments, crafting epistemic devices, and imagining new forms of ethnographic expression. The next question was no longer how to build it, but how to keep it alive.

References

- Collins, Samuel, Matthew Durington, and Harjant Gill. 2017. Networked Anthropology: A Primer for Ethnographers. Routledge.

- de Certeau, Michel. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. University of California Press.

- Drazin, Adam, and Susanne Küchler. 2015. The Social Life of Materials: Studies in Materials and Society.Bloomsbury.

- Gunn, Wendy, Ton Otto, and Rachel Charlotte Smith, eds. 2013. Design Anthropology: Theory and Practice.Bloomsbury.

- Ingold, Tim. 2011. Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description. Routledge.

- Ingold, Tim. 2013. Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. Routledge.

- Ingold, Tim. 2018. Anthropology: Why It Matters. Polity Press.

- Jackson, Steven J. 2014. “Rethinking Repair.” In Media Technologies: Essays on Communication, Materiality, and Society, edited by Tarleton Gillespie, Pablo Boczkowski, and Kirsten Foot, 221–239. MIT Press.

- Latour, Bruno. 1990. “Drawing Things Together.” In Representation in Scientific Practice, edited by Michael Lynch and Steve Woolgar, 19–68. MIT Press.

- Latour, Bruno. 2008. What Is the Style of Matters of Concern? Amsterdam: Van Gorcum.

- Law, John. 2004. After Method: Mess in Social Science Research. Routledge.

- Lury, Celia, and Nina Wakeford, eds. 2012. Inventive Methods: The Happening of the Social. Routledge.

- Manning, Erin. 2016. The Minor Gesture. Duke University Press.

- Manning, Erin, and Brian Massumi. 2014. Thought in the Act: Passages in the Ecology of Experience. University of Minnesota Press.

- Marcus, George E. 2013. “Experimental Forms for the Expression of Norms in the Ethnography of the Contemporary.” Hau: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 3(2): 197–217.

- Massumi, Brian. 2011. Semblance and Event: Activist Philosophy and the Occurrent Arts. MIT Press.

- Myers, Natasha. 2015. Rendering Life Molecular: Models, Modelers, and Excitable Matter. Duke University Press.

- Pink, Sarah. 2015. Doing Sensory Ethnography. 2nd ed. Sage.

- Rabinow, Paul, George E. Marcus, James D. Faubion, and Tobias Rees. 2008. Designs for an Anthropology of the Contemporary. Duke University Press.

- Rheinberger, Hans-Jörg. 1997. Toward a History of Epistemic Things: Synthesizing Proteins in the Test Tube.Stanford University Press.

- Schneider, Arnd, and Christopher Wright, eds. 2010. Between Art and Anthropology: Contemporary Ethnographic Practice. Berg.

- Stewart, Kathleen. 2007. Ordinary Affects. Duke University Press.

- Suchman, Lucy. 2011. “Anthropological Relocations and the Limits of Design.” Annual Review of Anthropology40: 1–18.