From The Atelier Series

Munich, 2017: The Artefaktenatelier

When I arrived in Munich to begin my doctoral research, I found myself surrounded by a language of precision—machines, diagrams, infrastructures, grids. The city seemed to operate as both laboratory and metaphor. It made me wonder whether ethnography could also become something other than narrative: perhaps a material experiment, a workshop of relations (Ingold 2013; Lury & Wakeford 2012).

That intuition became the Artefaktenatelier. The name itself—part German, part imagined—suggested a place where artifacts, not merely texts, could emerge as epistemological devices (Rheinberger 1997; Henare, Holbraad & Wastell 2007). It was not a research group or institutional lab, but a space where thinking and making came together, allowing ethnographic encounters to take the shape of diagrams, maps, installations, and prototypes (Marcus 2013; Schneider & Wright 2010).

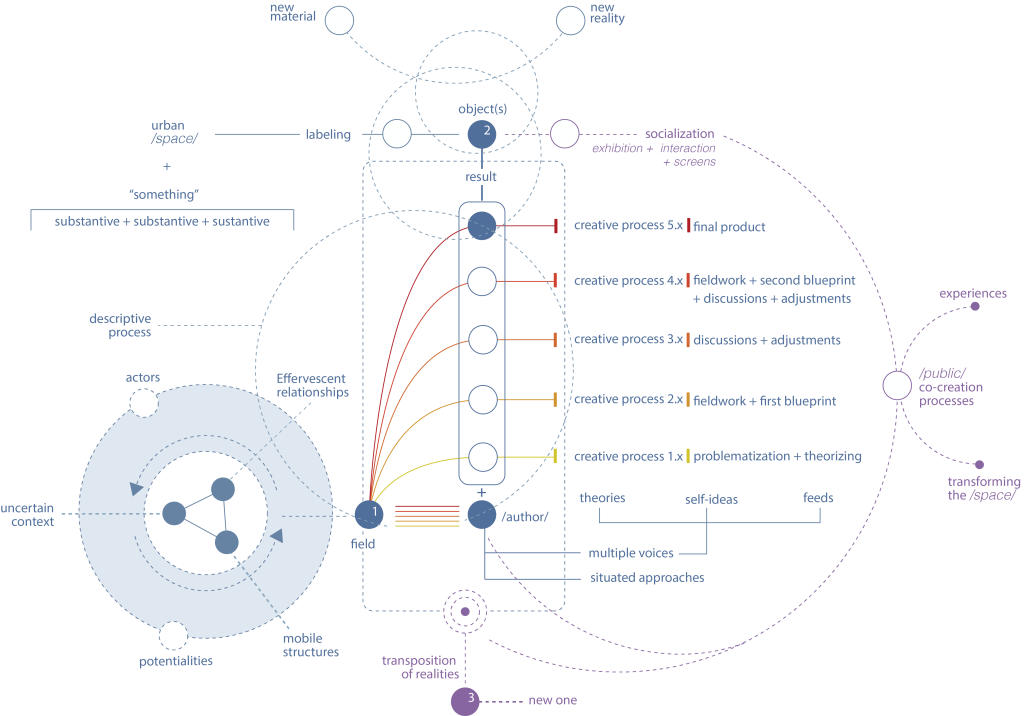

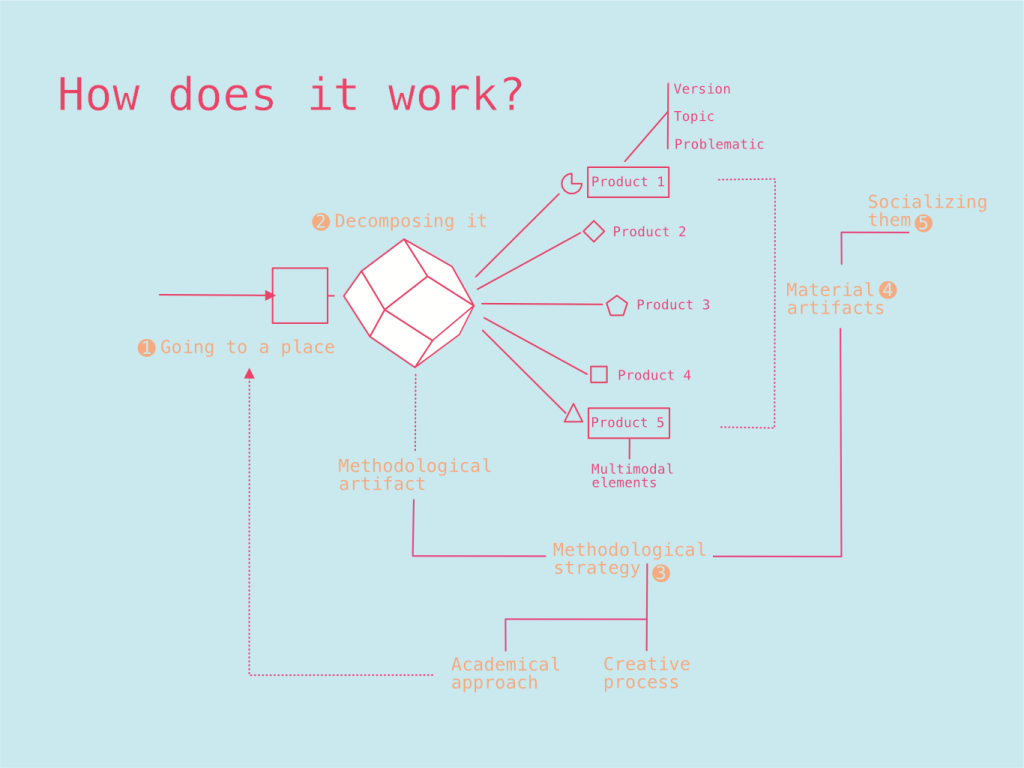

At the time, I felt the need to visualize how ethnography actually unfolds: not as a linear sequence of observation and writing, but as a recursive, dynamic process in which fieldwork, theory, and creativity continuously interweave. I drew the first diagram of the Artefaktenatelier to make this visible—a speculative map of relations rather than steps.

In that diagram, the “field” is not a location but an effervescent zone of relations (Latour 2005; Law 2004). Objects, actors, and ideas circulate through loops of theorizing, making, discussing, and reworking. Each iteration produces a “new reality,” a version of the city transformed by creative processes and public co-creation (Marres, Guggenheim & Wilkie 2018). It was an early visualization of ethnography as design—open-ended, recursive, and collective (Suchman 2011; Gunn, Otto & Smith 2013).

The drawing became a companion to my first field experiments. I began to see diagrams, field notes, and prototypes as equally valid modes of inquiry (Taussig 2011; Drazin & Küchler 2015). The Artefaktenatelier thus emerged not as a place of production but of transposition—where fragments of fieldwork could travel across media and become analytical artifacts in their own right (Myers 2015).

In retrospect, those first sketches were less about representing knowledge and more about cultivating sensitivity: to processes, to transformations, to the subtle ways realities multiply when they are drawn (Manning & Massumi 2014). The atelier became a way to live with that multiplicity—to remain in the recursive motion between knowing, making, and being affected (Puig de la Bellacasa 2017).

From this Munich desk, the foundations of what I now call the ethnographic studio were laid. The Artefaktenatelier taught me that ethnography could be multimodal, that its objects might be diagrams, maps, or prototypes, and that each of them could think in its own way. The rest of the story—Times Square, the labyrinth, and beyond—would grow from this first experiment.

References

- Drazin, Adam, and Susanne Küchler. 2015. The Social Life of Materials. Bloomsbury.

- Gunn, Wendy, Ton Otto, and Rachel Charlotte Smith, eds. 2013. Design Anthropology: Theory and Practice.Bloomsbury.

- Henare, Amiria, Martin Holbraad, and Sari Wastell, eds. 2007. Thinking Through Things: Theorising Artefacts Ethnographically. Routledge.

- Ingold, Tim. 2013. Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. Routledge.

- Latour, Bruno. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford University Press.

- Law, John. 2004. After Method: Mess in Social Science Research. Routledge.

- Lury, Celia, and Nina Wakeford, eds. 2012. Inventive Methods: The Happening of the Social. Routledge.

- Manning, Erin, and Brian Massumi. 2014. Thought in the Act: Passages in the Ecology of Experience. University of Minnesota Press.

- Marcus, George E. 2013. “Experimental Forms for the Expression of Norms in the Ethnography of the Contemporary.” Hau: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 3(2).

- Marres, Noortje, Nils Guggenheim, and Alex Wilkie, eds. 2018. Inventing the Social: Materiality, Movement, and the Methodological. Mattering Press.

- Myers, Fred. 2015. “The Art of the Anthropological Imagination.” Annual Review of Anthropology 44: 1–19.

- Puig de la Bellacasa, María. 2017. Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More-Than-Human Worlds. University of Minnesota Press.

- Rheinberger, Hans-Jörg. 1997. Toward a History of Epistemic Things. Stanford University Press.

- Schneider, Arnd, and Christopher Wright, eds. 2010. Between Art and Anthropology: Contemporary Ethnographic Practice. Berg.

- Suchman, Lucy. 2011. “Anthropological Relocations and the Limits of Design.” Annual Review of Anthropology40: 1–18.

- Taussig, Michael. 2011. I Swear I Saw This: Drawings in Fieldwork Notebooks, Namely My Own. University of Chicago Press.