Lately, I’ve been wondering what happens to Materialtone if I stop only looking at surfaces and start pressing against them. Until now, the project has been built from photographs, squares of color and texture sampled from walls, pavements, bollards, and doors. Each card isolates a chromatic fragment and treats it as a specimen. But walking around the city, I kept thinking about the other side of these surfaces—the way they grip shoes, collect dust, catch water. So I bought a block of pink modeling clay and tried a slight detour.

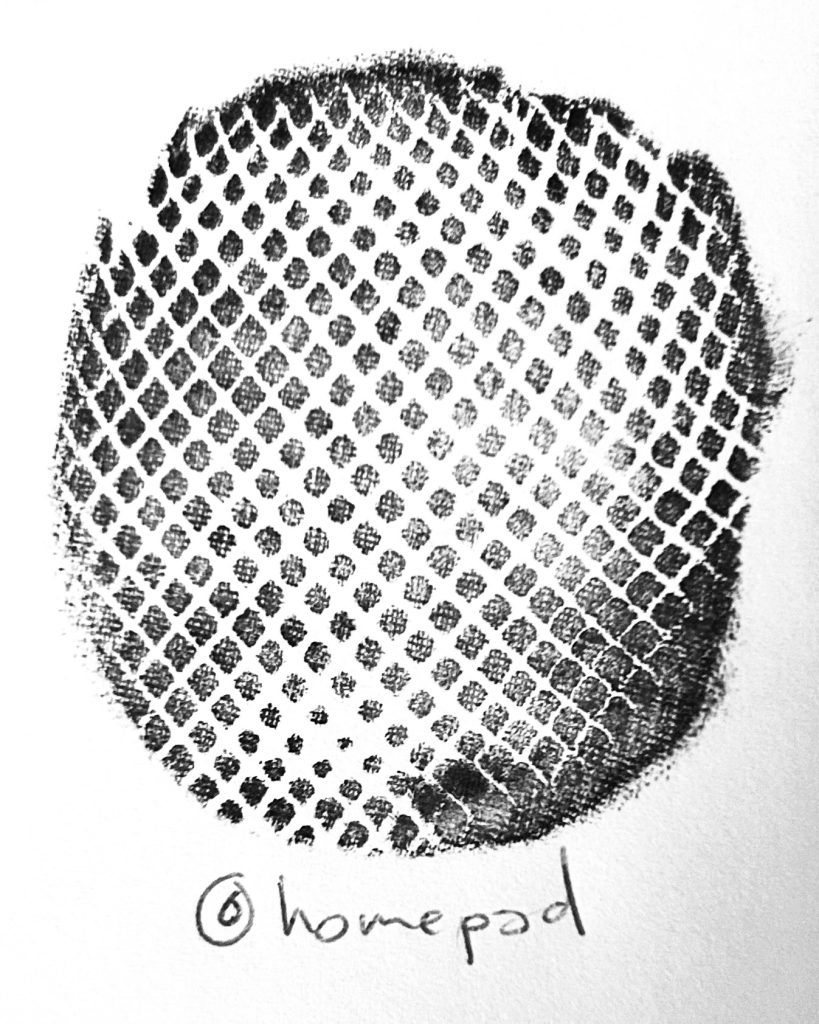

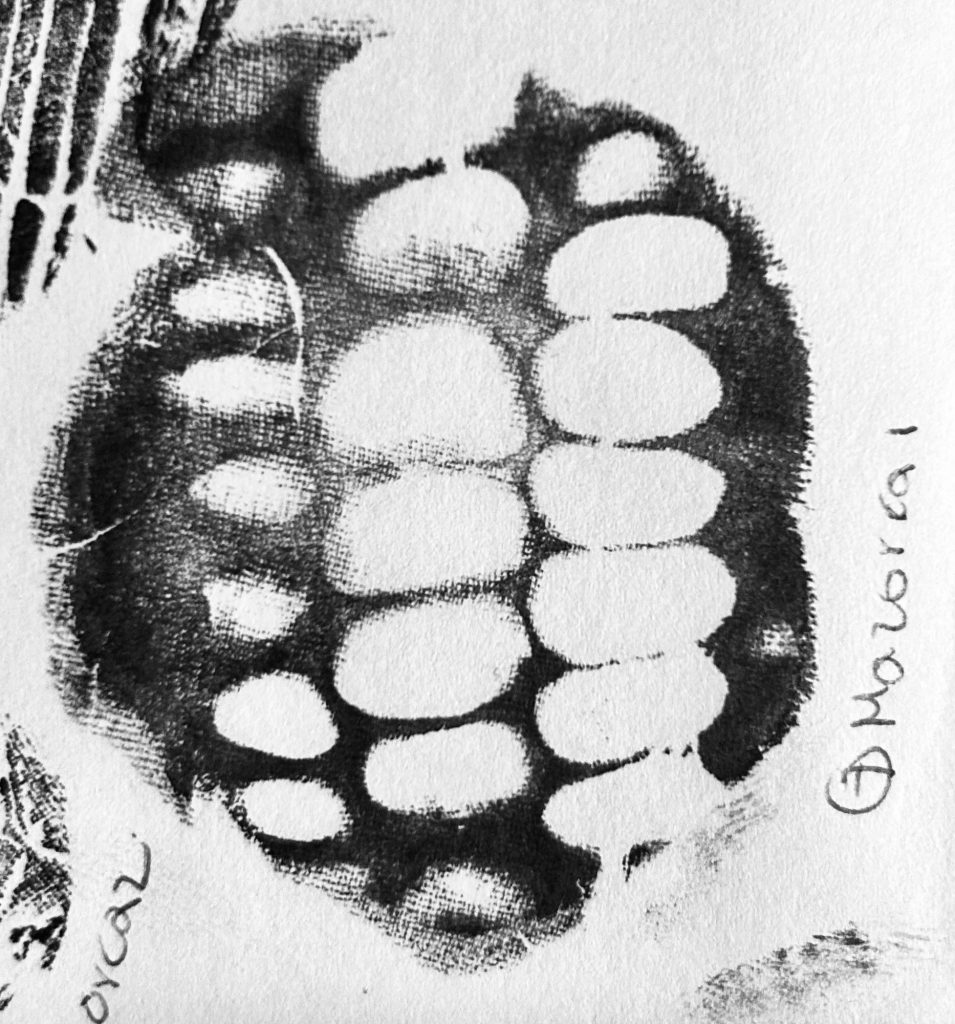

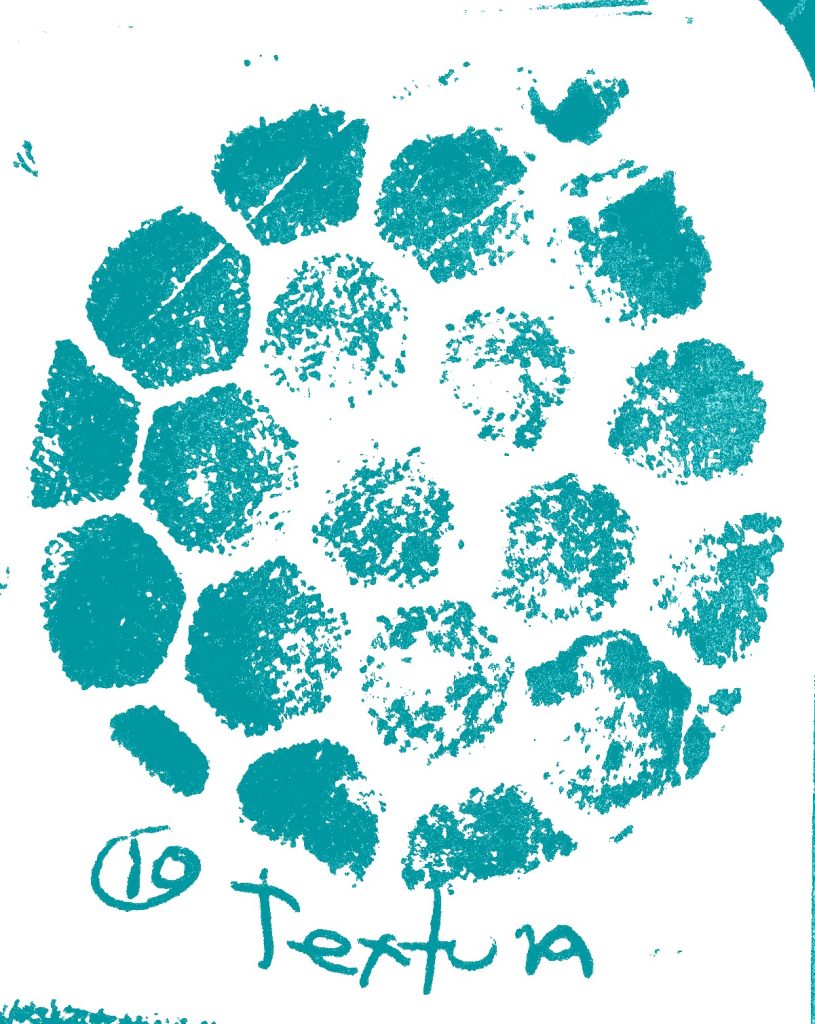

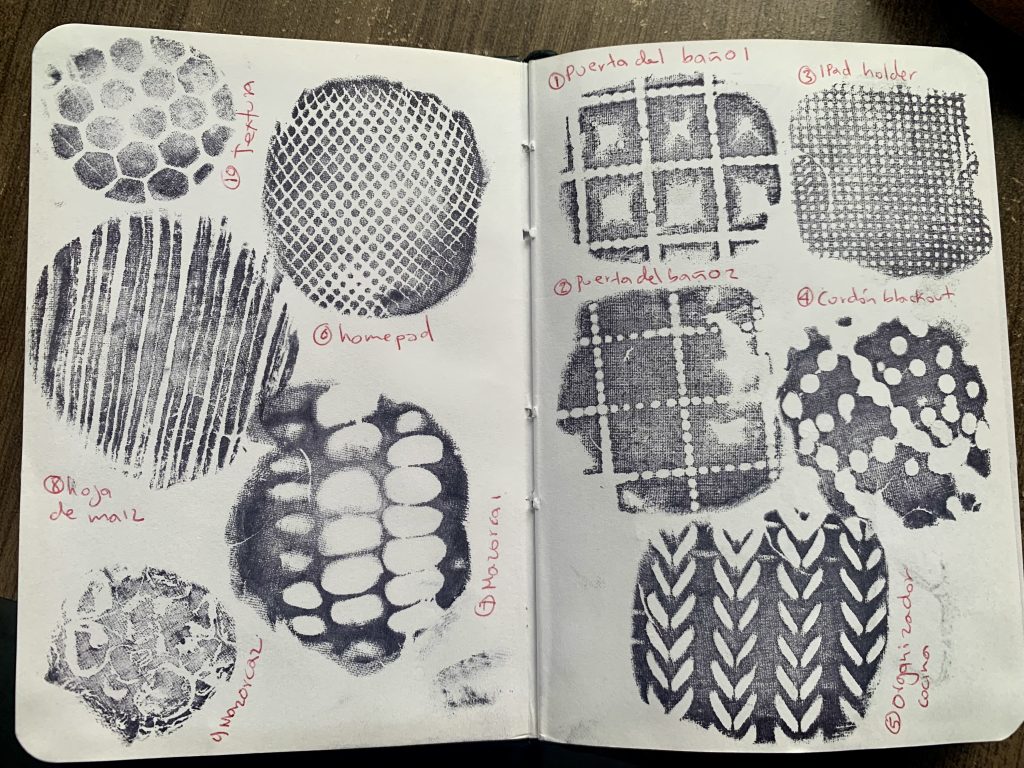

The first experiments happened at home. To conduct them, I used whatever was at hand: a silicone homepad, a kitchen “textura” tool, the veins of maize leaves, and the lids and handles of pots. I flattened the clay into small pads and pressed them firmly against each object. Once I inked them and later printed them in my sketchbook, the objects timidly reappeared as soft, lo-fi, and ephemeral lithographies: a dense grid of dots (HomePod), rounded hexagons (kitchen tool), and oval kernels (maize). These objects, translated into new media, looked like a low-cost cross between a printmaking test sheet and a forensic catalogue of domestic tools.

Images 2 and 3. Domestic experiments: maize and household objects turned into small lithographies.

What interested me the most was not only the pattern but the gesture behind it. Making these impressions required a small choreography and connection with the materials: kneading the clay until it was warm, centering it in the palm, choosing a spot, pressing, feeling the resistance, peeling it back, and checking whether the relief was legible. The prints carry this bodily sequence within them, along with the remains of previous attempts and old traces of ink. They are not images of an object but traces of a brief contact—clay and surface meeting under the pressure of my hand. At this point, I still wasn’t sure if this belonged to Materialtone or to some parallel project, but the textures were compelling enough to keep going.

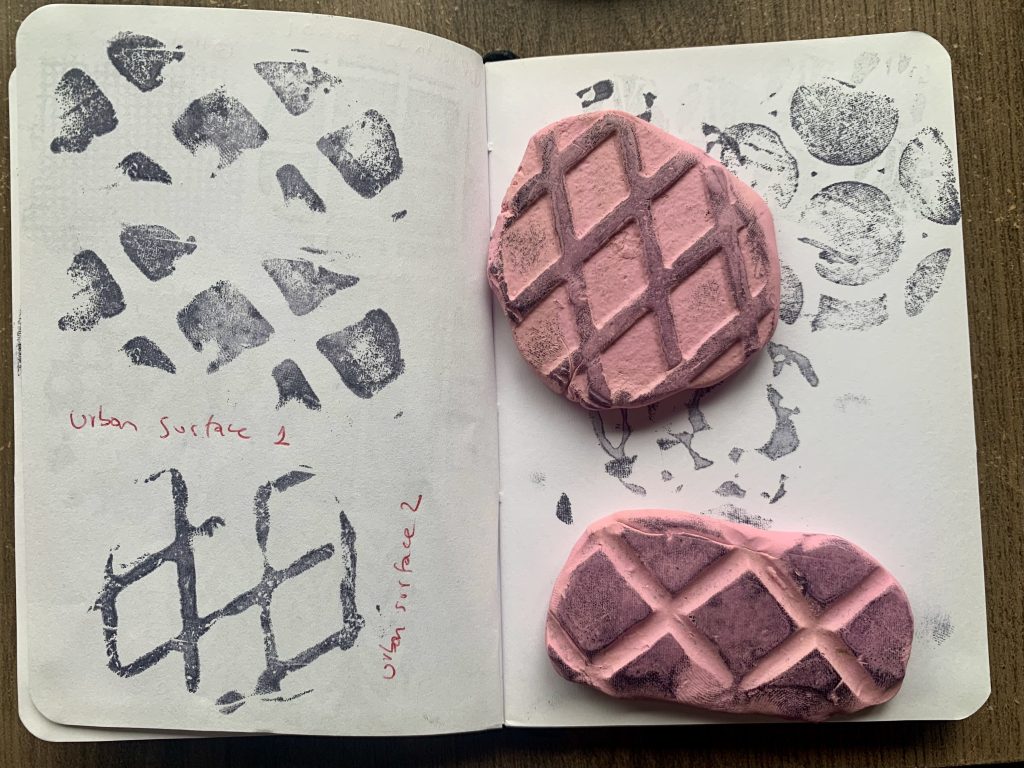

The next step was to take the clay out to the streets. I started with surfaces that already fascinated me chromatically: a turquoise utility cover with a raised diamond grid, a manhole whose rough metal is slowly whitening with wear. Kneeling on the sidewalk, I firmly pressed the pink pads onto the metal until the pattern pushed through, then lifted them carefully so they wouldn’t tear. Sometimes it didn’t work on the first attempt, so I had to repeat the process a couple of times. Finally, the impressions came out strong: diamonds in negative, letters reversed, tiny pits and scratches preserved as bumps. Back home, those same pads produced a sheet of “urban surface” prints—broken, misaligned clusters of shapes that still clearly belonged to the street.

Technically, the process is messy and full of small failures. If the clay is too soft, the pattern sags and prints as a blur. If it is too hard or too thin, it doesn’t pick up enough depth. Sometimes my own fingerprints sneak into the impression. Yet these imperfections feel right for Materialtone, where fragments are never clean samples but compromised, mixed-up pieces of infrastructure. Each pad becomes a portable fossil of a contact zone, storing in its surface both the city’s relief and the hesitations of my hand.

With these tests, tactile impressions have started to solidify as a new branch of the project: Materialtone / Reliefs. The idea is simple: for some surfaces, a color card will now have a tactile sibling. One is made from pixels, the other from pressure. The turquoise photograph of the street cover can sit next to a monochrome print of its diamond grid, later recolored using the same tone. Together, they show not only how the city looks but how it feels when it pushes back. The sketchbook spreads, the stained clay pads, and the digital recolorings form a small chain of translations: surface → impression → print → card.

For me, the most important consequence is methodological. These impressions behave like field notes—not written descriptions, but hand-sized records of encounters. A walk for Materialtone now involves two parallel forms of sampling: pointing the camera at patches of color and pressing clay against patches of texture. Both require slowing down, crouching, and touching the city in slightly awkward ways. In that sense, tactile impressions are not just an aesthetic upgrade; they are a way to thicken the ethnographic practice within Materialtone, letting the city write itself into the archive through the pressure it leaves on a soft, pink surface.