This is the first entry of a series of five posts on an ethnographic experiment on my garden in Lübeck, northern Germany, whose simple goal was nothing more than decomposing that terrain through the fabrication of detailed descriptions and graphic artifacts. This is then an epistemological exercise that mixes a multiplicity of ethnographic multis: multispecies, multisensorial, and multimodal accounts with the elaboration of multimedia products to try to translate and organize a multiple and multiontological urban scenario. Overall, the whole experiment has two particularities. (1) It has been proposed as a multimodal autoethnography. (2) Its multimedia core comprises literary vignettes and data visualizations.

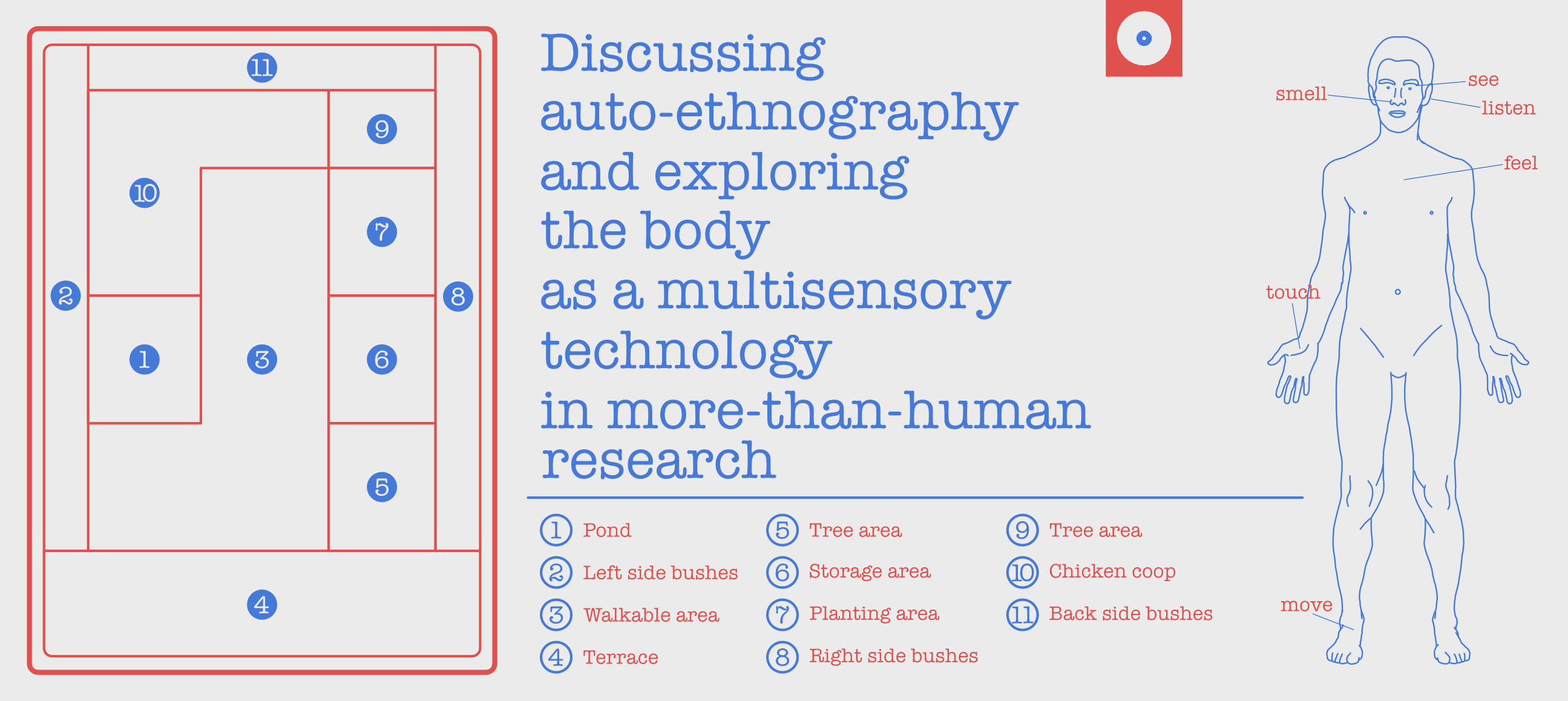

However, the scope of this series is much more modest. It attempts to introduce two main concatenated contributions to the study of more-than-human relationships in urban environments. The first one is the exploration of multimodality as an epistemological workbench, accentuating its core neither on the side of the fabrication of epistemological devices (audiovisual and performative products) nor in the usage of multimedia artifacts such as cameras or phones but on the ethnographer as a multisensory machine. The second one takes the figure of the ethnographer —as an embodied technology to see with their body— and uses it to construct an autoethnography that will serve as a methodological thread to combine multimodal and sensory accounts to explore more-than-human urban entanglements.

The essay picks up Ingold’s discussion on Merleau-Ponty’s (1962) notion of the human body as a “subject of perception” (Ingold, 2000, p. 169), taking it from that phenomenological perspective to a postphenomenological frame that conceives the ethnographer as a mediated, multimodal, and multisensorial technological artifact. I plan to use the concept of oligopticon (Latour and Hermant, [1998]2006), a metaphor borrowed from Actor-Network Theory, to enrich and expand the conversation of the ethnographer as an embodied multisensorial piece of technology. In general terms, the whole experiment —as well as this paper in particular— was inspired by the good spring weather yet to come and Marris’ (2011) Rambunctious Garden, especially by her idea of how humanity has lost nature not just because we have destroyed it but due to we have displaced it.

Our mistake has been thinking that nature is something ‘out there,’ far away. We watch it on TV, we read about it in glossy magazines. We imagine a place, somewhere distant, wild and free, a place with no people and no roads and no fences and no power lines, untouched by humanity’s great grubby hands, unchanging except for the season’s turn. This dream of pristine wilderness haunts us. It blinds us. (Marris, 2011, p.1).

Being-in-the-garden

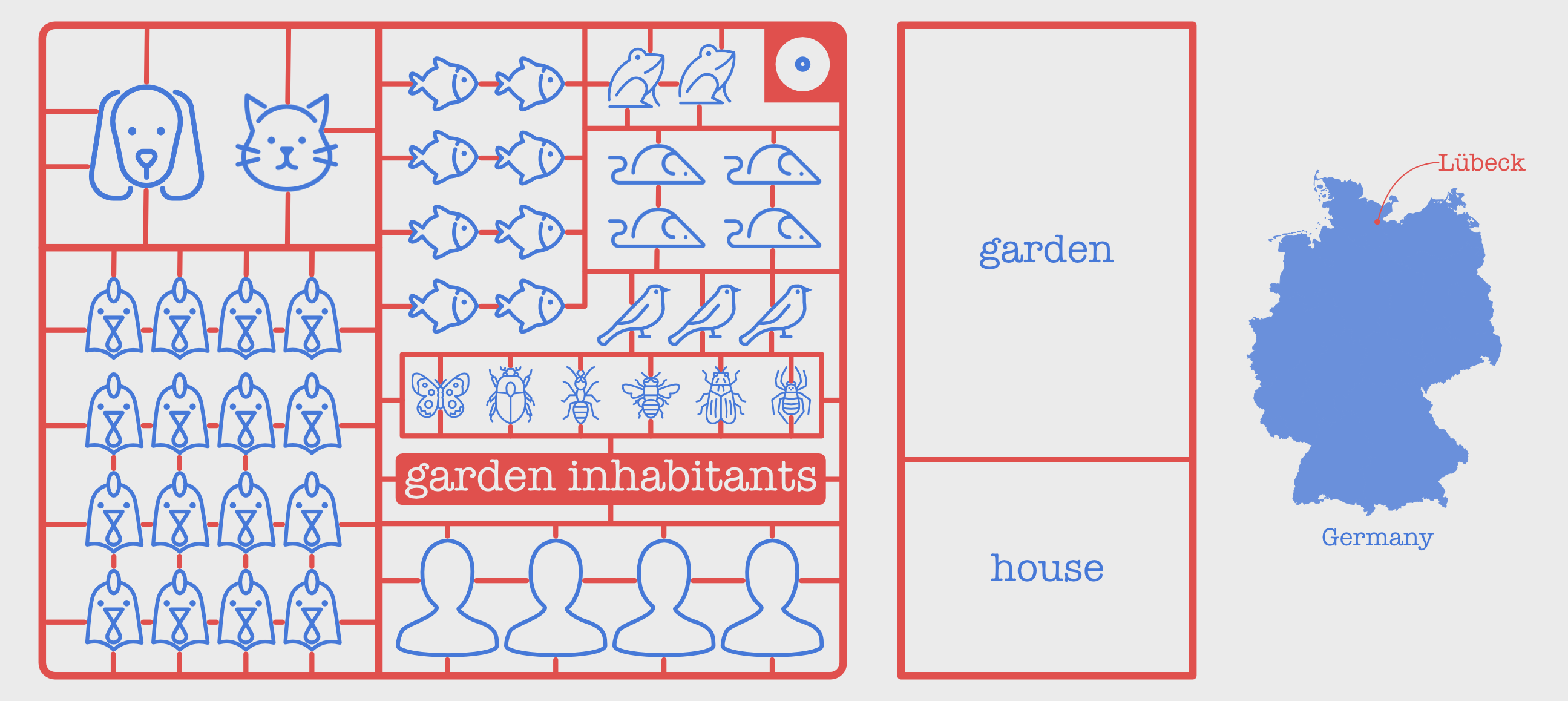

I live with three people, a cat, a dog, 16 chickens, and eight fish. We live in between a two-story house and a backyard that is three times bigger than the house. The backyard also has its own habitants: frogs, mice, birds, and a broad variety of insects. The house is in a neighborhood near a field and a small forest. The neighborhood, the field, and the forest are part of the suburban area of a small city, Lübeck, located in northern Germany. Neither the fish nor the chickens —except for one or two chickens a couple of times— live inside the main house. The fish share a pound, and the chickens a large coop composed of a huge red house, two areas for laying and hatching eggs, and a vast field for carving, taking sand baths and exploring around.

Early in the morning —the exact time depends on the season— I go to the backyard to open the chicken house and give them some food and fresh water. After that, I did not use to see the chickens anymore —although I heard them from time to time— until the end of the day when I came back to their coop to close their house door and collect their eggs. Regarding the fish, I barely have contact with them. It is not just that we are in different environments but also that they are not my responsibility. The garden division of work includes the four humans doing all kinds of tasks, the chickens laying eggs, and the cat hunting —and almost all the time catching— mice and, eventually, small snakes.

Even though I have been living in that location for almost four years, it was just recently that I started to pay serious attention to the structure, relations, and elements inhabiting the garden with us. I am not just talking about the chickens and the fish; I am also referring to the rest of the living and nonliving things occupying, affecting, and being interlaced in that limited environment: birds, frogs, moles, mice, insects, plants, weather, rocks, soil, water, and so on. Since I am an ethnographer, my gaze and primary resources are based on and limited to ethnographic observation. However, the type of observation ethnography provides me generally goes beyond a single sense.

Being-in-the-garden, as an insinuation to Heidegger’s ([1962]2008) being-in-the-world, represents an embodied immersion where “the self and the world merge in the activity of dwelling so that one cannot say where one ends and the other begins” (Ingold, 2000, p. 169). The self, as perceptive materiality, as a body, defined by Merleau-Ponty (1962, p. 2) —and quoted by Ingold (p. 169)— as “the vehicle of being in the world,” was my primary device for approaching that unexplored territory I had at the back of my house and that as in Marris’ (2011, p. 3) rambunctious garden, was creating “more and more nature as it goes.”

References

- Heidegger M (2008[1962]) Being and Time. New York: HarperCollins.

- Ingold T. 2000. The Perception of the Environment: Essays in Livelihood, Dwelling, and Skill. London: Routledge.

- Latour B. and Hermant E. [1998]2006. Paris: Invisible City. Retrieved from: http://www.brunolatour.fr/sites/default/files/downloads/viii_paris-city-gb.pdf.

- Marris E. 2011. Rambunctious Garden: Saving Nature in a Post-Wild World. New York: Bloomsbury USA.

- Merleau-Ponty M. 1962. Phenomenology of perception. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.